The next time a top U.S. conducting post comes open, expect James Gaffigan to be high on the list of candidates. After all, the American conductor was singled out by New York Times critic Anthony Tommasini as among the possible “heartening left-field picks” for the recently filled music directorship of the New York Philharmonic. That’s quite a boost, given that Gaffigan is just 37 years old and only 12 years away from being a first-prize winner in the influential Sir Georg Solti International Conducting Competition.

“I was lucky to have great people around me from the beginning, keeping things calm,” said Gaffigan, who just received a Gramophone Award for his Warner Classics recording with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony and Vilde Frang in the Britten and Korngold Violin Concertos. “In the music world, it’s very easy to be a flash in the pan and disappear. Saying no to things early on when you’re not ready is key.” He praised in particular the advice and guidance he has received along the way from orchestra members, especially those at the Cleveland Orchestra, where he was an assistant conductor from 2003 through 2006. “Bill Preucil, the concertmaster, would call me aside: ‘You don’t need to subdivide this. Just trust us here, and we’ll do it.’ Or someone in the back of the violin section would say, ‘Look at us, we need the contact.’ Little things like that, you don’t learn in school or you don’t learn from any conductor. You learn from a few special people in every orchestra that you trust.”

Gaffigan will return to Oct. 6-8 to lead the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the world premiere of Australian composer Carl Vine’s Five Hallucinations for Trombone and Orchestra with CSO trombone Michael Mulcahy as soloist. The conductor estimates that he is involved with some kind of debut at least every other month and enjoys being “a part of something coming to life, especially when there is a soloist involved, because often these pieces are written for that person, and you can see changes that happen along the way,” he said. Gaffigan worked with Wynton Marsalis on his Concerto in D (for Violin and Orchestra), which received its world premiere in November with the London Symphony Orchestra and famed soloist Nicola Benedetti, helping the composer make a few changes to the piece. (The work, a co-commission of the Ravinia Festival, had its U.S. premiere in July, with conductor Cristian Măcelaru leading the CSO.) “It’s exciting to me that it’s a process,” he said. “It’s not just: Here is my piece, perform it and then go home.”

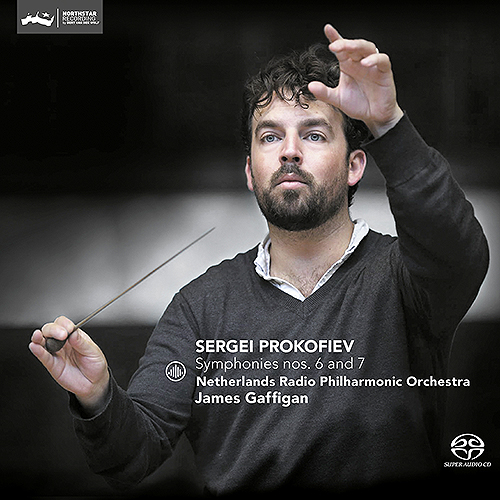

James Gaffigan is currently recording a complete cycle of Prokofiev symphonies with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra.

What he notices first with any composer, Gaffigan said, is whether he or she possesses a distinctive musical language. “With the Vine [Trombone Concerto], it’s clear that it’s really well-crafted, and it’s not thankless. Many pieces I’ve done, there is so much work for the orchestra musicians to do, and in the end, nobody really realizes it. Whereas, with something like Tom Adès, you put in the work, and you get a great result. You get something extremely special. I think this piece is very realistic with the orchestration and how much time we have to put it together.”

Along with his guest conducting work, Gaffigan has served as chief conductor of the Lucerne Symphony Orchestra since 2010. In June 2015, his contract was extended through 2022, a testament to his success in the post. Under his leadership, the orchestra has toured Europe, Asia and South America, and made a few well-regarded recordings on the prestigious Harmonia Mundi label.

“There are two reasons I extended for so long,” he said. “No. 1 is artistically, I can’t imagine a better place to be working. I have a great partnership with my intendant [executive director]. He’s a genius and he’s a fund-raising machine, and artistically we’re both on the same page. I just think the orchestra is extraordinary, and it couldn’t be replicated anywhere else in the world. And secondly, our audience base — we’re like 96-97 percent sold all the time. We have a very dedicated group of people who live in Lucerne and come from across Switzerland, Italy and France to be subscribers. It’s an extremely special place.”

Gaffigan lives in Lucerne because of his position with the orchestra but also because of its centrality in Europe, which gives him easy access to the rest of the continent. “And it’s just a beautiful quality of life,” he said. In addition, he serves as principal guest conductor of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra and the Gürzenich Orchestra in Cologne, Germany, and has become a frequent guest conductor with many of the world’s leading orchestras and opera companies. In December, for example, he made his debut with the New York Philharmonic, conducting a program that included the world premiere of Split, a fantasy for piano and orchestra by Andrew Norman. In an enthusiastic review, Tommasini praised both the new work and Gaffigan, writing that the conductor brilliantly oversaw the performance.

Of that experience, Gaffigan said, “Of course, being a New Yorker and going to the New York Philharmonic for the first time was very intimidating, but I found them to be great people the second I went onstage.” He was impressed that the orchestra was able to learn and perform Norman’s challenging piano concerto in a short time and elegantly pull off the works by Ludwig van Beethoven and Richard Strauss on the same program. “They really want to work, which I think is great,” he said. “A big misconception, especially among young conductors, is: ‘They’re not going to want to work. They won’t want to hear anything I have to say.’ I think the truth is that if a conductor is prepared and does have something to say, the musicians are willing to listen.”

Along with his orchestra work, Gaffigan has done a significant amount of opera conducting, including four summers at England’s Glyndebourne Festival and with such companies as the Vienna State Opera and Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich. In September and October, Gaffigan will lead seven performances of The Marriage of Figaro with the Washington National Opera, and he has upcoming productions scheduled at the Metropolitan Opera and Lyric Opera of Chicago. He calls leading an opera from the pit an entirely “different beast” than conducting a symphony orchestra onstage. “I need opera in my life,” he said. “I need the theater in my life. It’s one of my favorite things to do. It’s really necessary for me to work with singers. They’re crazy and I love them at the same time. To accompany a great singer, there is nothing like it in the world.”

Believing early in his career that recording was a dying art form, Gaffigan is a relative latecomer to this world. But the more he thought about it and the more he worked with orchestras, he realized that significant swaths of the repertoire have been little recorded or not at all. His first release on Harmonia Mundi with the Lucerne Symphony was devoted to the works of Wolfgang Rihm, and his second featured Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6 and the American Suite. For a different label, he is putting the finishing touches on a complete set of the Prokofiev symphonies with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic. “I’ve been lucky to work with great engineers who are as picky as I am,” he said.

Gaffigan’s disc of Tchaikovsky and Prokofiev concertos, with Kirill Gerstein, won Germany’s ECHO Klassik Award.

Earlier this year, an album he recorded on the Myrios Classics label was nominated for a BBC Music Magazine Award and won an ECHO Klassik Award, Germany’s top such classical honor. It was the first recording of a newly published urtext or original edition of the 1879 version of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1, with pianist Kirill Gerstein and the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin.

In 1894, a third edition of the concerto was published — a flashier version with modified tempos and articulations and an entire section cut from the third movement. Recent research shows that this long-accepted version of the concerto is not one that the composer actually wrote. Though no conclusive connection exists, evidence points to Alexander Siloti, a student of Tchaikovsky, as the likely instigator of this later, suspect edition. “What didn’t help is that Mr. Siloti had a good talent for self-promotion,” Gerstein said in a Sounds and Stories interview published last year, “so he said that, absolutely, Tchaikovsky knew about and had said this was the way to do it. But it turns out, when the facts are investigated, that the neither the dates nor any sources confirm that Tchaikovsky knew about this or authorized this.” Despite the apparent divergence from the composer’s wishes, that later version gradually became standard.

Opening Gaffigan’s CSO concerts, in the first of two narrative bookends, will be César Franck’s Le chasseur maudit (The Cursed Huntsman). “It’s so great and I think many people don’t know it and haven’t played it,” he said. The work spotlights the French horn section, and the CSO has a well-regarded tradition of horn playing. As the symphonic poem tells the story of a nobleman who makes the mistake of hunting on the Sabbath, it features what Gaffigan calls some “terrifying” music, including a witches’ dance. “It’s a very audience-friendly piece, because it tells a story from beginning to end,” he said.

As a closer, Gaffigan wanted to perform music by Prokofiev, which he believes plays to the CSO’s strengths. “The different colors and the different timbres of sound in the Prokofiev symphonies and ballets are really fun to explore with an orchestra that is as good and as versatile as the Chicago Symphony,” he said. Gaffigan chose the composer’s balletic adaptation of Cinderella, because it is a little less known than some of the Russian composer’s other works. Featured will be 45 minutes of excerpts that follow the arc of the fairy tale, with all its elements of humor and romance but also ugliness and cruelty. “I think it is an audience pleaser and I think it is an orchestra pleaser,” he said. “I think people really like digging in and playing this music.”

The symphonic world has no doubt taken notice of Gaffigan and his potential, and he acknowledges that he would like eventually to lead an American orchestra. “But the right one has to come at the right time,” he said. “And I think there is no rush.”

Kyle MacMillan, former classical music critic of the Denver Post, is a Chicago-based arts journalist.