In 1908, before Chicago had a Wrigley Field, baseball fans watched the Cubs win the World Series — at Orchestra Hall.

“Baseball was king,” the Chicago Daily Tribune reported, “And nowhere was its title more vociferously recognized than in the temple Chicago has dedicated to classical music.”

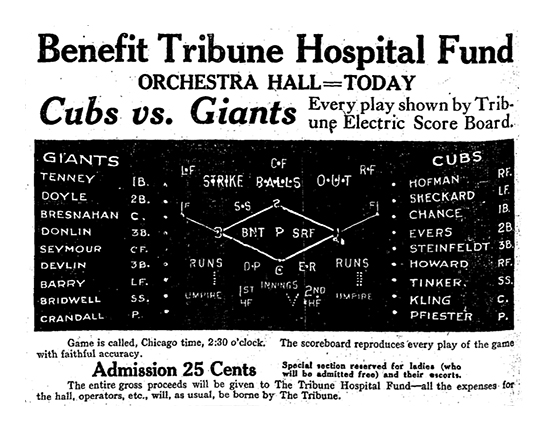

A Sept. 23, 1908, ad extols the Orchestra Hall scoreboard that “reproduces every play of the game with faithful accuracy” — but it missed the notorious “Merkle’s boner” that afternoon, and announced a Giants win that wasn’t.

Years before baseball took to the airwaves in 1921, fans nationwide followed important out-of-town contests via play-by-play wire accounts posted in theaters and public squares, with local newspapers assisting. Forerunners of today’s television score bugs and smartphone gamecasts, chalkboards with scores and easels with lineups, and later mechanical diagrams with flashing lights, kept fans current on counts, outs and base runners.

On Sept. 23 of that 1908 season, Orchestra Hall opened its doors for away games — admission, 25 cents for men, ladies free — beginning with a contest between the Cubs and New York Giants, tied in the race for the National League pennant. Once inside the hall, fans watched a manually operated display called “The Tribune Electric Score Board,” on a relay from the Polo Grounds. The paper described the machine as “a large blackboard sprinkled with 18 names, many mysterious letters, a geometrical diagram, and red and white electric lights.”

(Presumably the Electric Score Board rebroadcast or retransmitted its account of the game without the “express written consent” of the Chicago National League Ball Club, now prohibited.)

Despite assurances that “the scoreboard reproduces every play of the game with faithful accuracy,” on that afternoon, it missed the most notorious and consequential force-out in baseball history — and erroneously reported a Giants’ win that wasn’t. In fact, the Cubs’ pennant hopes remained strong. According to the Tribune, fans left dejected from Orchestra Hall when they should have been celebrating:

The flashing lights indicated that with two men out in the second half of the ninth inning of the Cub-Giant baseball game in New York, one Mr. Birdwell had landed on the ball and driven in the winning run [from third]. That made the score 2 to 1 in favor of New York, so the cheers and laughter were hushed in Orchestra [H]all, the great pipe organ, which had been pouring out the strains of “There’ll Be a Hot Time,” accompanied by a thousand voices, suddenly dropped into the mournful cadences of Chopin’s Funeral March, and all except a few loyal White Sox rooters filed sadly and solemnly from the hall.

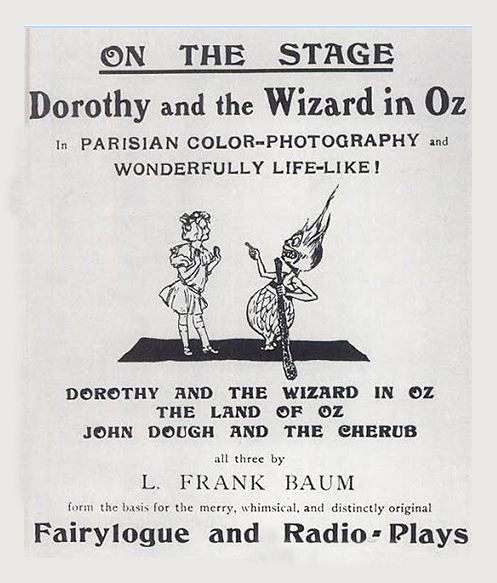

The second half of Orchestra Hall’s doubleheader on Oct. 2, 1908 was L. Frank Baum’s “Fairylogue and Radio-Plays.”

But in New York, one Mr. Merkle, on first base, filed happily and foolishly from the Polo Grounds without stepping on second, leaving an inning-ending force out alive. Mistakenly thinking the game had finished, the Giants’ Fred Merkle made for the clubhouse; meanwhile, the Cubs, with fielding better set to Chopin’s frenetic Minute Waltz, found the forgotten ball somewhere in left field, or maybe center field — or even wrestled the ball from the grandstand — and tossed it through an infield flush with Giants revelers (accounts vary) for the third out at second, scratching New York’s winning run. Night fell on the ninth-inning free-for-all, and the National League nixed the Giants victory, ruling the game a tie instead.

The notorious base-running error, quickly dubbed “Merkle’s boner,” forced a season-ending replay on Oct. 8, another game relayed from the Polo Grounds to Orchestra Hall. Tied that morning in the National League standings, the second-chance Cubs swept past the Giants, and into the 1908 World Series.

(Orchestra Hall also hosted the Cubs’ win on Oct. 2 at Cincinnati; that afternoon’s scoreboard operator alternated with a nighttime production of L. Frank Baum’s “Fairylogue and Radio-Plays,” which featured The Wonderful Wizard of Oz author sharing the stage with orchestra players and hand-painted films in what might be considered a precursor of today’s CSO at the Movies concert series. No doubt that daytime and evening audiences were warned, “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!”)

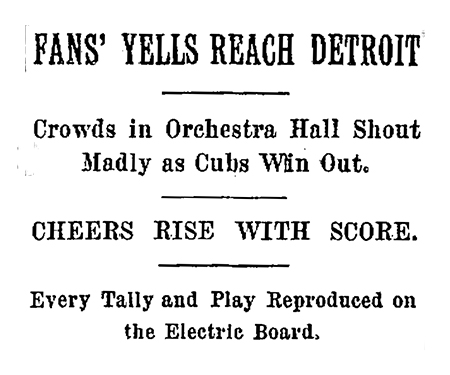

Headlines of a Chicago Daily Tribune report after Game 1 of the 1908 World Series, which fans “watched” at Orchestra Hall.

The 1908 World Series started on Oct. 10, with the Cubs in Detroit. After Game 1, the Tribune wrote: “Never in its history did the staid home of the Thomas orchestra hold within its walls such a wild, insanely enthusiastic demonstration.” (The Theodore Thomas Orchestra, then named for its founding conductor, was rechristened the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1913.) “Between innings the crowd sang and whistled and the great pipe organ played ragtime.”

The paper’s anonymous account reads like program notes written in Ring Lardner style for Richard Strauss’ Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks, a Thomas orchestral favorite, reveling in “tidal waves of enthusiasm that swept men and women, young and old, rich and poor, to the most extravagant demonstrations of joy and sorrow”:

Through all the rest of that momentous third inning while the Cubs were piling up four runs, knocking [Detroit pitcher Ed] Killian out of the box, and apparently clinching the game, there was hardly an instant that hundreds of men and boys, yes, and women and girls, too, were not on their feet cheering the runners, encouraging the batter, joining the pitcher, and rooting with all their might for victory.

More than a century of autumns has passed since crowds in Orchestra Hall shouted madly for hometown players besides the classical musicians of their mighty CSO. This season especially, and definitely once again, fans of ballgames and symphonies at Chicago’s temple of music are expecting remarkable Fall Classics.

Andrew Huckman is a Chicago-based lawyer and writer.

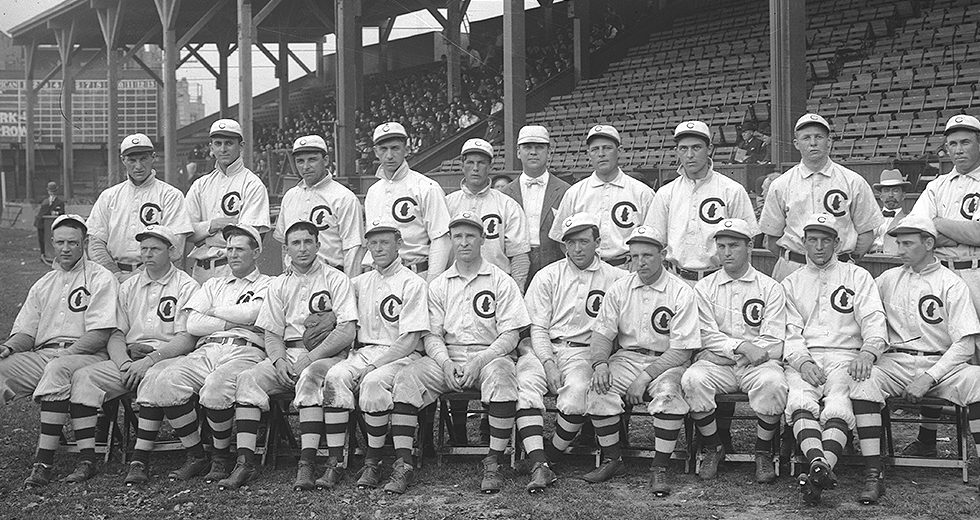

TOP: The 1908 World Series champion Chicago Cubs. | Photo: Library of Congress