Symphony Center hosts plenty of piano supporters. Front and center, there’s none stronger and more steady than Orchestra Hall’s piano lift — hauling up to 2,000 pounds of Steinway, Yamaha, Bechstein and Bösendorfer at 25 feet per minute.

The piano lift — an elevator, really — easily handles 990-pound Steinway Concert Grands with room to spare — almost nine inches either side and just over 14 at both ends. Bösendorfer Imperial? No problem — its nine extra keys clear with 10 extra inches.

The downstage lift, just shy of 75 square feet, sits slightly stage left. It rests below the conductor (as in “Riccardo Muti,” rather than “high voltage” — then again …), and section leaders for second violin, viola and cello. Mechanical lock bars keep the lift flush with the stage, eliminating vibration and ensuring it doesn’t drop mid-performance — which might trigger a chaotic jumble of screaming string principals, motors and hydraulics in the manner of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Helicopter String Quartet.

And, yes, there’s a framed City of Chicago Certificate of Inspection. The elevator inspector shows up, Symphony Center stage technicians roll out the piano, then electricians run the motorized pump till the city signs off.

* * *

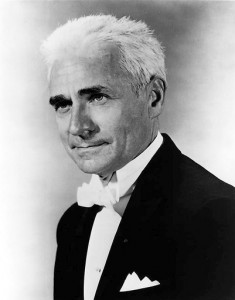

Orchestra Hall’s piano lift was installed for the autumn 1966 CSO season, when French conductor Jean Martinon (below right) was music director, the White Sox were finished, and Space Age television was packed with NASA missions and sci-fi drama “Lost in Space” (“Danger, Will Robinson! Danger!”)

A few blocks south, the Auditorium Theatre (the CSO’s home before Orchestra Hall opened in 1904) underwent modernization from 1964 to 1967. The CSO, concerned about its own aging facility, hired the Auditorium’s renovation architects and engineers, led by Chicago preservation specialist Harry Weese, for Orchestra Hall’s extensive spring-summer 1966 overhaul. Weese gave special attention to stage and mechanical systems, lifts included. In a year filled with Gemini rocket launches, Chicago piano fans first cheered “We have liftoff!” on Oct. 6 when John Browning’s Steinway rose to the stage for Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1.

A few blocks south, the Auditorium Theatre (the CSO’s home before Orchestra Hall opened in 1904) underwent modernization from 1964 to 1967. The CSO, concerned about its own aging facility, hired the Auditorium’s renovation architects and engineers, led by Chicago preservation specialist Harry Weese, for Orchestra Hall’s extensive spring-summer 1966 overhaul. Weese gave special attention to stage and mechanical systems, lifts included. In a year filled with Gemini rocket launches, Chicago piano fans first cheered “We have liftoff!” on Oct. 6 when John Browning’s Steinway rose to the stage for Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1.

It’s less likely the Orchestra Association eyed Comiskey Park’s imaginative renovations in 1960, when colorful White Sox owner Bill Veeck pushed his 1910 venue into the modern era apparently with an underground baseball-delivery system. Kansas City Athletics owner Charlie Finley perfected it in 1961 by installing, as Sports Illustrated reported:

A rabbit with blinking eyes, wearing an A’s home uniform, that rises from an invisible spot in the grass to the right of the plate umpire. Between the ears of the rabbit, who is called Harvey, is a cage of baseballs. The cover magically flings itself open and the umpire helps himself. The ascent of the rabbit is accompanied by an ascending whistle, while his disappearance into the ground is accompanied by a descending whistle. Simultaneously the organist plays “Here Comes Peter Cottontail.”

Whistles, organs and costumed bunnies aside, it’s difficult discounting similarities to the CSO’s hidden piano lift — flashing lights included.

A rotating yellow safety beacon, visible just below stage, appears whenever Orchestra Hall’s piano lift is in motion. (“Danger, Jean Martinon! Danger!”) The only other time CSO players encounter a safety beacon is at Ravinia Festival’s annual “Tchaikovsky Spectacular” — a fixed red light near Gate 1, flipped midway through the 1812 Overture, warns that cannons are armed and ready.

“Going down?” The lift descends from stage level via the use of a wired, hand-held remote control; the control’s buttons are recessed and covered to prevent inadvertent triggering. Usually the control’s handled by CSO Stage Manager Kelly Kerins or Chief Electrician Robert Stokas. There’s an extra control downstairs, locked in an adjacent closet, in case — well — someone loses the remote. It hasn’t happened yet.

Once the lift is downstairs, barriers enclosing the shaft open, and the piano slides on or off. The piano’s wheels remain unlocked during the ride, but no concert grand has rolled off so far.

* * *

The lift, installed during an era of Space Race tensions, started something of a piano arms escalation, with France the first victor. In the lift’s second season, Martinon’s final, he invited compatriots Robert, Gaby and Jean Casadesus to join the CSO in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 7 for three pianos on Oct. 12, 1967. Reviewing the husband, wife and son ensemble, the Chicago Tribune bemoaned “probably Mozart’s least appealing concerto, bland in the gallant mode of the time, with few moments of sparkle and little beyond surface elegance to justify raising and lowering the stage elevator three times in mid-performance.”

Other memorable nights of load-bearing virtuosity: CSO Music Director Sir Georg Solti celebrated his 75th birthday, pushing the “Up” button twice, joining Murray Perahia in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 10 for two pianos on Oct. 9, 1987. Principal Guest Conductor Claudio Abbado joined Principal Piano Mary Sauer and keyboardist David Schrader in 1985 — all three on harpsichords — in the Bach C Major Piano Concerto, to mark the composer’s tricentennial. And Music Director Daniel Barenboim fêted the 25th anniversary of his CSO debut, sharing Mozart Piano Concerto No. 7 keyboards with wife Elena Bashkirova and longtime collaborator Radu Lupu in early 1996.

The moral for mere mortals? Don’t keep hitting the elevator button unless you’ve got a really good reason.

* * *

Ever wanted to ride the piano lift during a performance? Unless you’re one of Kerins’ stage technicians or Stokas’ electricians — stoic and silent in their black suits, descending like pallbearers at Mr. Baldwin’s funeral — you won’t finagle it.

Ever wanted to ride the piano lift during a performance? Unless you’re one of Kerins’ stage technicians or Stokas’ electricians — stoic and silent in their black suits, descending like pallbearers at Mr. Baldwin’s funeral — you won’t finagle it.

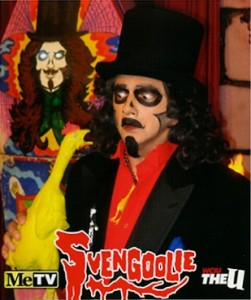

Instead, Svengoolie it. Over the lift’s 48 seasons, it seems only one artist has ascended during an Orchestra Hall performance: Svengoolie (a.k.a. Rich Koz), the Chicago-based host of Me-TV’s eponymous Saturday-night bastion of schlock horror and Space Age mutants. Koz, who was joined by Civic Orchestra conductor William Eddins for a “Hallowed Haunts” concert on Oct. 30, 2003, remembers his 47-second rise to glory: “I recall being down below the stage, with a couple of stagehands at the ready, and, as artificial fog rolled on the stage above, we began a VERY slow ascent to the stage level … and I do mean SLOW. We became visible to the audience, and received thunderous applause — which, if I remember correctly, died down somewhat before we actually stopped moving.”

(Kerins, who was on hand below, is certain “Svengoolie rode the piano lift up while reclined on a piano.”)

“It was actually quite overwhelming to get up to stage level and see the entire house before us,” Koz recalls. “We also departed the stage on the lift … again, very slowly. I think the Navy Pier Ferris wheel moves slightly faster.”

Get used to it, Svengoolie. The days of maestro Martinon conducting Paganini’s Moto perpetuo, for orchestra with piano accompaniment, are long gone. Expect no more perpetual-motion keyboards at Orchestra Hall. Since 1966, the speed limit for pianos has remained 25 feet per minute.

Andrew Huckman is a Chicago-based lawyer and writer.

VIDEO: Shot and edited by Todd Rosenberg, © Todd Rosenberg Photography