When the Chicago Symphony Orchestra performs George Gershwin’s iconic tone poem An American in Paris as part of its “Gershwin Spectacular” concert March 24-25, patrons will hear a familiar sound starting roughly a half-minute in and repeated at various points soon thereafter: old-fashioned taxi horns. Thanks to some recent scholarly sleuthing, we now know more about the history of Gershwin’s hand-picked honkers than ever before. There’s even a CSO connection. First, though, some background.

Nine decades ago, in late February of 1929, Gershwin visited Cincinnati, shortly before two early-March performances of An American in Paris by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. It was the piece’s first foray outside New York, where it had premiered at Carnegie Hall the previous December and on national radio in late January.

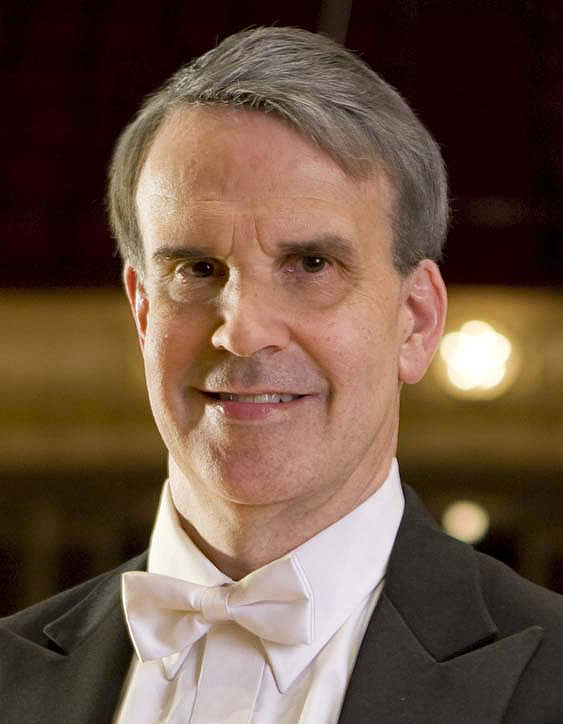

CSO percussionist James Ross. | ©Todd Rosenberg Photography

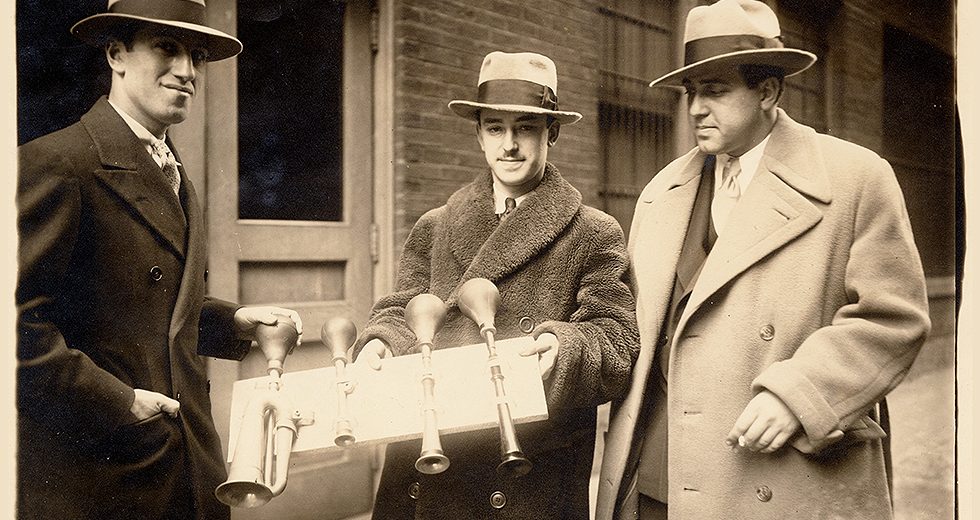

During his Ohio jaunt, Gershwin posed for photos with several other men, including Cincinnati’s principal conductor Fritz Reiner (who later became the CSO’s music director) and percussionist James Rosenberg. In one shot, provided to the University of Michigan from the digital collection of the Ira and Leonore Gershwin Trusts of San Francisco, Gershwin and Rosenberg each hold one end of an odd-looking contraption consisting of four different-sized French taxi horns (the squeezable kind with a rubber bulb) fastened to a wooden board. Gershwin, who purchased the horns in Paris, incorporated them into his score to evoke the hustle and bustle of Paris street life. Making their first appearance in measure 30, they are played as a series of accented eighth notes. So as to indicate which horn to honk when, Gershwin labeled their entrances with circled letters: A, B, C and D. Since at least 1945, on countless sets of horns, those letters have been interpreted as notes — and as gospel. But are they really?

A few months after the New York Philharmonic gave the premiere of An American in Paris at Carnegie Hall and a few weeks before Gershwin arrived in Cincinnati, he had supervised a Victor Recording of the piece in which the horns sound distinctly different than those to which audiences and listeners worldwide have long become accustomed. They sound, in fact, much more like they look in that 1929 photo. Instead of A, B, C and D natural, their pitches — A-flat, B-flat (above middle C), high D and low A (a third below middle C) — are more dissonant and whimsical-sounding — even a bit comical. Perhaps, as some now surmise, orchestras have played the parts incorrectly all this time.

Mark Clague, an associate professor of musicology at the University of Michigan and editor-in-chief of the school’s Gershwin Critical Edition, certainly thinks so. It was his research on the topic that prompted stories in the New York Times, on National Public Radio and elsewhere.

But unconvinced is veteran CSO percussionist Jim Ross, the son of late Cincinnati percussionist James Rosenberg, who eventually moved his family to Chicago to begin a CSO residency of his own that lasted 13 years. Ross has played Gershwin’s masterpiece (and its deceptively difficult-to-operate taxi horns) more times than he can remember. (In the CSO’s performances March 24-25, Vadim Karpinos, CSO assistant principal timpanist, will handle the honkers.) While he’s intrigued by the discussion of alternate pitches and even finds the pitches themselves somewhat enjoyable, he remains skeptical that the composer intended musicians to play something other than what they’ve always played.

“The pitches that we’ve used all these years around the world fit into the harmony and the orchestration and the trumpet parts, and they sound right,” he says. Could they be wrong? Sure. “The question is: Are you open to it?”

After his father died in 1980, Ross came across a photo of Rosenberg standing with Gershwin, Reiner and two other men — a prominent vocalist of the day and the orchestra’s manager — all of them dressed in sharp suits, fedoras and overcoats. Taken during the same session that produced the Gershwin Trusts’ picture, that shot also shows Rosenberg holding the taxi horn apparatus, his right hand grasping one of its bulbs. The instrument, however, is largely obscured from view. Until seeing the photo of Gershwin and Ross’ father prominently displaying the horns last year, Ross was unaware of its existence. Not only that, he says, his dad never even mentioned the Gershwin encounter. He’s not sure why.

“You’d think he would have,” Ross says. “If it had been me, I would have showed it to my kids. ‘Hey, look at this!’”

Mike Thomas is a Chicago-based journalist and novelist.

TOP: Composer George Gershwin (from left), percussionist James Rosenberg and tenor Richard Crooks pose with the original taxi horns used for the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra’s performances of An American in Paris on March 1-2, 1929. | PHOTO COURTESY OF THE IRA AND LEONORE GERSHWIN TRUSTS