Abraham Lincoln, whose Springfield-bound funeral train stopped in Chicago days after his assassination 150 years ago on April 14, fascinates Gene Pokorny.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s usually ebullient principal tuba recounts the solemn tale of a “dark, rainy, early morning — pre-dawn darkness,” when a “whole town has turned out to stand along the railroad tracks, because that was when Lincoln’s funeral train was coming through the town of Dublin, Ind. They’re going to pay homage to their fallen leader. He was on his way back home.”

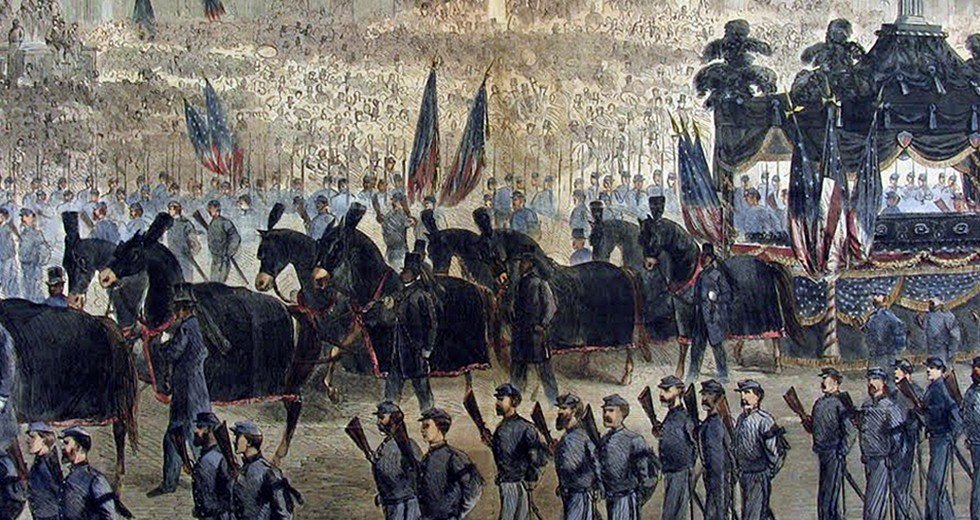

On the next day, which was May 1, 1865, President Lincoln returned to Chicago, as 10 black horses drew his hearse from the train depot north along Michigan Avenue. Mourners gathered where Orchestra Hall now stands.

Inside the hall, the CSO’s resident rail buff sports a collared shirt embroidered “Union Pacific,” the iron highway that Lincoln authorized in 1862. Pokorny observes that construction was launched with the “goal of getting a railroad from the Union states all the way to the Pacific,” while the embattled president simultaneously struggled to hold North and South together — “a fight for America’s own soul; the country trying to figure out what the future was going to be.”

Though Pokorny remembers a leader of broad human and geographic vision, he grapples with whether Lincoln’s long-ago message of union and progress, and legacy of liberty and sacrifice, still register — and what role Chicagoans and CSO musicians share in keeping that history forceful and resonant. “This thing 150 years ago, it’s very hard for people to get all welled up inside.”

Enter Citizen Musician, the initiative of the CSO Negaunee Music Institute, which pairs the conviction and artistry of Chicago’s musicians with the communities they engage. Citizen Musician sees opportunity in Pokorny’s enthusiasm for Lincoln, and so it will present two brass performances of Civic War-era music selections linked by Pokorny’s narration. Joining Pokorny (on his York tuba) will be CSO colleagues David Griffin on horn, Tage Larsen on trumpet and Michael Mulcahy on trombone, along with percussionist James Ross and others.

Together they will attempt to reveal new relevance in distant sadness during their Lincoln-themed concert April 17 at Benito Juarez Community Academy, the public high school in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood.

Lincoln (1809-1865) and Benito Juarez (1806-1872) aren’t the curious fit they first seem. Juarez, the president of a warring Mexico whose May 5, 1862, triumph against occupying French forces at the Battle of Puebla nowadays invites a legacy of excessively marketed and oft-misunderstood commemorations, was the voice for his own nation’s democratic ideals. Together, Lincoln and Juarez reflect an era aspiring to national union and individual liberty.

Pokorny, who also happens to be the CSO’s biggest Three Stooges fan, no doubt recognizes that trivializing Civil War sacrifice seems as wrong as today’s Corona-fueled Cinco de Mayo TV advertising. Despite his love for all things Stooges, he’s steering clear of the comedy trio’s Civil War-themed material in his Lincoln project. That material includes the Stooges’ “Uncivil Warriors” send-up, from 1935 (“Your names will be Lieutenant Duck, Captain Dodge and Major Hyde. … Duck! Dodge! Hyde!”), and the wartime marching song “Listen to the Mocking Bird,” which a bemused Lincoln once declared was “as sincere as the laughter of a little girl at play.” Decades later, the Stooges used the song as a soundtrack for their chorus of “soitenlys,” “why, I oughtas” and “nyuk, nyuk, nyuks.”

The solemn war years didn’t always lack levity. “The generals in the army wanted the brass bands of the time to play in an upbeat, major key so that they wouldn’t get the soldiers down,” Pokorny mentions while discussing music for the Lincoln concert. “Some of these sad tunes are played in an upbeat way, which is going to be a little bit of a juxtaposition.”

So will opera. “It seemed to be a popular thing at the time — that [military bands] would actually do music from operas back then,” Pokorny says. So he’s including rousers from Ernani and Il Trovatore, both by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), the celebrated son of Italy’s Risorgimento political movement.

Like Lincoln in America, like Juarez in Mexico, Verdi spent the early 1860s serving a uniting homeland born on enlightened principles. The composer served a term in Italy’s first parliament, from 1861 to 1865, which overlapped the years of the U.S. Civil War.

“Verdi, as strong a musical figure as he was, was probably very much a strong political one,” Pokorny says. “The Italian public loved this guy and what he did for nationalism.” His festive opera selections welcomed dignitaries on American railroad platforms, too — notably, Pokorny recalls, New York’s Seventh Regiment Band playing under the wartime direction of a composer-arranger named Claudio Grafulla.

Pokorny has a talent for highlighting the musically improbable, whether it’s Grafulla’s Union fondness for Italian marches or Lincoln’s affection for “Dixie,” the divisive, unofficial Confederate anthem that Honest Abe favored at 1860 campaign rallies. The tuba player notes that the song “had nothing to do with the South. It was a tune that came out of Ohio. Somehow it got wrangled around.”

“When the war ended, Lincoln requested that the U.S. Navy band play ‘Dixie,’ which was the headstrong song of the South, but he said, ‘Now that they lost the war, this song belongs to all of us.’ ”

How — and whether — Verdi’s triumphs, the divisive “Dixie” and a host of 1860s band tunes still evoke the legacy of Lincoln’s victory and tragedy with Chicago’s modern compatriots remains Pokorny’s inspiration, concern and, perhaps, reward. “I don’t know how this is going to go over,” he says. “We have mostly Civil War music, which is very simple — some would think simplistic.” It’s so simple that “we’re close to it sounding like the Three Stooges.”

Soitenly not.

Pokorny and his CSO colleagues will debut their Abraham Lincoln tribute beginning at 9:30 a.m. at Benito Juarez, then will rush from the Civil War to World War II for Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 8 (1943) later that day at 1:30 p.m. in Orchestra Hall. The Lincoln commemorative program will be repeated at 10:30 a.m. April 20 at the Chicago History Museum. At Juarez, Mario Rossero, chief of curriculum of Chicago Public Schools, will read Pokorny’s narration, while at the History Museum, Russell Lewis, the institution’s executive vice president and chief historian, will do the honors.

Pokorny also will be a soloist for a second Chicago History Museum commemoration May 1, marking the sesquicentennial of the Lincoln funeral train stop in Chicago.

Andrew Huckman is a Chicago-based lawyer and writer.

TOP: Illustration of Lincoln’s hearse as it was transported across New York City.