Richard Strauss didn’t live to hear his Four Last Songs performed, although in a sense it didn’t matter, for the lovingly remembered, long since faded soprano of his wife Pauline was the only voice he would have wanted to hear singing this music.

Richard Strauss and Pauline de Ahna made an unusually powerful, if often volatile, match. They met in 1887 — she was 25, he 23 — before either of their careers had taken off, and once they married, seven years later, they became the music world’s most celebrated couple, although his fame and success as a composer continued to soar while her days as a leading soprano would soon be over. The ups and downs of their long marriage were chronicled not only in the stories fondly recalled by friends and family, but also in Richard’s music itself, beginning with the full-length, not-always-flattering portrait of Pauline played by the solo violin in Ein Heldenleben in 1899, and climaxing, in 1924, when Richard turned one of their habitual marital spats into his new opera, Intermezzo.

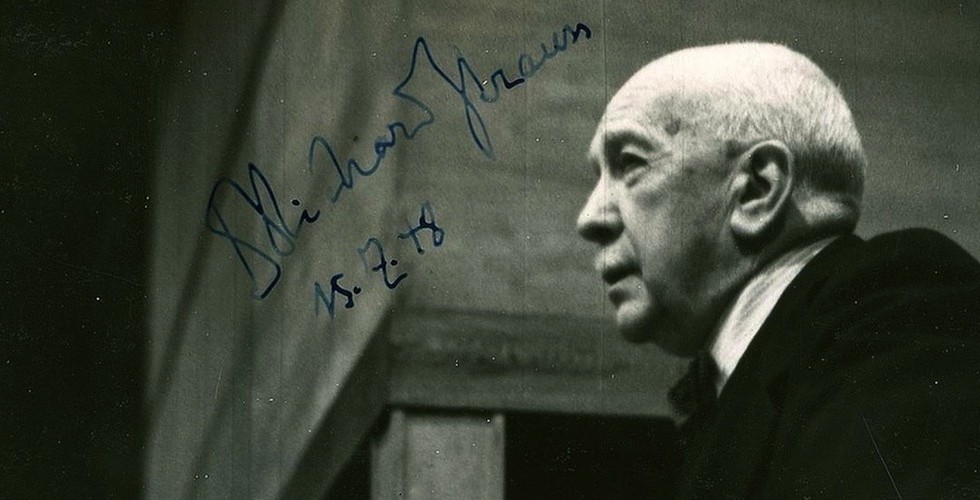

In the autumn of 1947, their marriage stronger than ever (inexplicably to many who had witnessed its daily storms) after 53 years in each other’s company, Strauss read a poem by Joseph Eichendorff that struck him like a thunderbolt. Im Abendrot tells of a couple at the end of their long lifetime together — hand in hand, as Eichendorff says — now facing death. Outwardly Strauss brushed aside all thoughts of his — and Pauline’s — mortality with his characteristic dry wit. (A reporter in London, where Strauss went that fall to attend a festival of his music, asked the 83-year-old composer of his future plans. “Oh,” Strauss said, without missing a beat, “to die.”) But the setting of Im Abendrot, which he began that year, suggests how deeply he felt about a subject he couldn’t bring himself to address, except in music.

He and Pauline had been through so much together, from the dazzling early successes (the royalties from Salome alone built them the villa in Garmisch where they lived out their days) to the public failure of his recent music and the fear and anxiety of the Hitler years, when the life of his own Jewish daughter-in-law was in jeopardy. By 1947, Strauss knew that their best times were over, and that the world he had once known and loved and — perhaps more than any composer of the 20th century — conquered, was now almost unrecognizable. But he had no way of putting all that into music until an admirer gave him a book of poetry by Hermann Hesse, the 1946 recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Strauss read Hesse’s poems not only with the thrill of discovery (Hesse wasn’t yet widely known, and far from the cult figure he would become), but also with the pain of recognition, for in these pages he saw himself and Pauline — hand in hand — facing their last days together. He immediately picked several poems to set to music. In the end, he wrote just three songs that, together with Im Abendrot, extend his farewell to life and to love. He worked on virtually nothing else during the summer of 1948, and when these songs were done, he found that he had little energy left.

The following May, Strauss and Pauline moved back to the Garmisch villa they had been forced to abandon at the height of the war. The night before his 85th birthday, he somehow found the strength to travel to Munich for the dress rehearsal of Der Rosenkavalier, which had provided one of the greatest triumphs of his career 37 years before. Strauss was asked to conduct brief portions of the opera — a rather sad and dispiriting stunt that was captured on film, to the continuing detriment of his reputation as a great conductor.

In August, he had several mild heart attacks at his Garmisch home and began to fail quickly. Near the end, he is reported to have turned to Alice and said, “Dying is just as I composed it in Death and Transfiguration.” But that was a young man’s idea of death as a great, transcendent experience — a spectacular ending provided for a blockbuster tone poem by its fearless and callow 25-year-old composer. Sixty years later, Strauss was bedridden; Pauline had been an invalid for some time. Despite his clever words, he couldn’t dictate his own final chapter. But Strauss had always clung to his myths. At the end of Im Abendrot, when Eichendorff wonders “Could that be death?” Strauss changed das to dies, and asking instead “Could this be death?” he quotes the quiet, rising theme from his Death and Transfiguration.

In September, Strauss died at home in his sleep. Pauline died the following May, just nine days before the premiere of her husband’s — and in the deepest sense, her — four last songs. They were immediately acclaimed as among the very finest of Strauss’ achievements — music for which his entire career was preparation. Little in his output can match the beauty and depth of these songs — from the transparency of the orchestral writing, with its burnished horn solos and shim mering birdsong, to the radiant soprano lines — rising on Lüften (“skies”), taking off in breathless flight at Vogelsang (“birdsong”), and—in one of the most unforgettable moments in music — soaring in phrases of pure rapture, to match the violin’s lofty melody at Seele (“soul”).

A last few words. Since Strauss never dictated that these four songs were to be performed as a set, he indicated no particular order. At the premiere, they were sung neither in chronological order nor in the sequence that is now customary. It was Ernst Roth, the composer’s friend and publisher, and the dedicatee of Im Abendrot, who later established the performance order and provided the not-quite accurate title that has stuck, Four Last Songs. In fact, we now know of a fifth song, written for voice and piano, Malven, that was composed later in 1948 for the soprano Maria Jeritza, who kept it hidden in her New York apartment until her death in 1986, when it was discovered among her papers. A few measures of sketches for yet another Hesse song were left unfinished on Strauss’ desk at his death.

Phillip Huscher is the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.