How does a conductor lead an orchestra in the performance of a live movie score? It’s bit like the “how do you get to Carnegie Hall?” axiom: practice, practice, practice.

“It’s all in the preparation,” said conductor Richard Kaufman, who directs many of the CSO at the Movies concerts (and who will be on the podium for all three series events this season: “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial,” “Amadeus” and “North by Northwest”). “I’m a preparation fanatic, so when I stand in front of an orchestra, my job is to be completely prepared and to do everything I can to make the whole process as easy and fulfilling as possible for the musicians.”

For each new score, Kaufman estimates that he usually spends about six months to a year studying and preparing it, as was the case for “The Wizard of Oz” (1939) and “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952). “Those films are especially complicated because they are, in a sense, Broadway shows with lots of singing and dancing as well as underscore [music heard under the dialogue].”

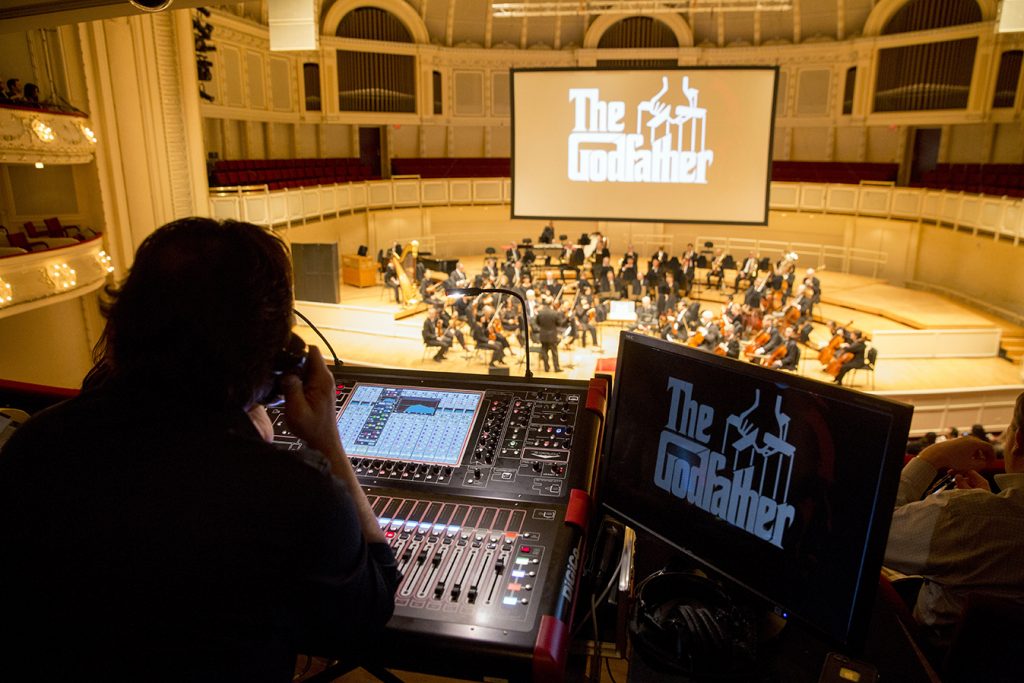

Members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra perform “The Godfather,” which features a landmark score by Nino Rota. | © Todd Rosenberg Photography 2015

CSO at the Movies programs fall into a category known in the industry as “live to picture”: musicians perform a film’s score while the complete movie is screened above the stage. The CSO introduced this kind of programming more than 25 years ago, but it took off with the launch in 2004 of Friday Night at the Movies (later renamed CSO at the Movies). Jim Fahey, director of programming for the CSO’s Symphony Center Presents, oversees the series, and with Kaufman, has shaped its evolution. “We look to feature the finest film scores that are available,” Fahey said. With its Oscar-winning score by John Williams, “’E.T.’ fits into that category,” he said. “The same goes for ‘Amadeus’ [with music by Mozart] and ‘North by Northwest’ [with a score by Bernard Herrmann].”

The live-to-picture movement has boomed in the last decade, with companies such as Film Concerts Live!, CineConcerts and John Goberman’s Symphonic Cinema among the leaders in this field. They negotiate performance rights, supervise the creation of the musicians’ sheet music, and technically make the movies stage ready. “For a film to be screened live with an orchestra, the music first needs to be removed from the soundtrack,” Kaufman said. “For older films, the original orchestra track was married to the dialogue and sound effects, and so the music must be erased wherever there is no dialogue or sound effects. Where there is music under dialogue, the music remains in the background. However, on the podium, although I can hear it in my audio monitor, when orchestra plays live, the audience doesn’t hear it.”

Contemporary films, Kaufman said, present fewer issues because “the score is on what’s called a music stem, and after it’s removed, you’re left with only dialogue and sound effects.”

The growth of digital technology has streamlined the performance process but these concerts still demand a conductor schooled in the art of directing live to picture. To keep the orchestra in sync with the movie, the conductor usually relies on either a click track (an in-ear metronome) or visual streamers (lines shown on a conductor’s monitor that indicate musical sync points). Both methods originated during the early days of sound movies. “Clicks function like a metronome,” Kaufman said. “They’re essential for a dance-oriented film like ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ to maintain synchronization.” In addition, Kaufman occasionally uses a third, low-tech method: a clock with a sweep hand. For silent films, “all the technology is between my ears,” Kaufman said, laughing. “You just have to know every scene of the film and hit exactly the right spots on basically every moment of the film.”

From the box tier, a technician monitors the live-to-picture presentation of “The Godfather.” | © Todd Rosenberg Photography 2015

As for the orchestra, limited rehearsal time is usually the norm. “We’ll have one rehearsal on the day of the show,” Kaufman said. “The players will have studied the music. We will rehearse certain scenes that need more than one look and then play through the score, skipping the dialogue scenes … always working on the music.”

Fahey and Kaufman point to the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s 1987 live-to-picture concerts of “Alexander Nevsky” (with Sergei Prokofiev’s landmark score) as the moment when orchestras realized the artistic potential of pairing music with moving images. The CSO presented its first live-to-picture event just a few years later.

“From the beginning, our goal was finding the best way to marry film with live orchestra,” Fahey said. “We did it first with silent films.” In 1991, the CSO performed “Love” (1927), starring Greta Garbo, with an original score by CSO violin Arnold Brostoff. A decade later, it offered Charlie Chaplin’s “City Lights” (1931) on the CSO subscription series. Both events were highly regarded, Fahey said, “so we have a long history with this tradition.”

In the first years of CSO at the Movies, primarily silent films were available for the format, “with only four or five titles we were aware of,” Fahey said. To round out the series, the CSO added clip shows (themed excerpts from several movies). “But all of a sudden, [live-to-picture] titles started to become available, and the series started to feature more and more feature-film concerts, including ‘West Side Story,’ ‘Casablanca’ and a premiere of ‘The Bride of Frankenstein,’” he said.

The ultimate star, Fahey and Kaufman emphasize, is the CSO itself. “The reason this series is such a success is due to the skill and brilliance of the orchestra,” Kaufman said. “It’s amazing what they have done with such incredibly complicated music, in limited rehearsal time. It’s a challenge that is met head on by the musicians and staff. Frankly, it boggles my mind how incredible they are.”

Along with the CSO at the Movies series dates of Nov. 25, April 18 and May 26, there will non-subscription concerts of “E.T.” on Nov. 26-27 and “Amadeus” on April 19. In addition, tickets are available for a live-to-picture presentation of “It’s a Wonderful Life” on Dec. 9-11.