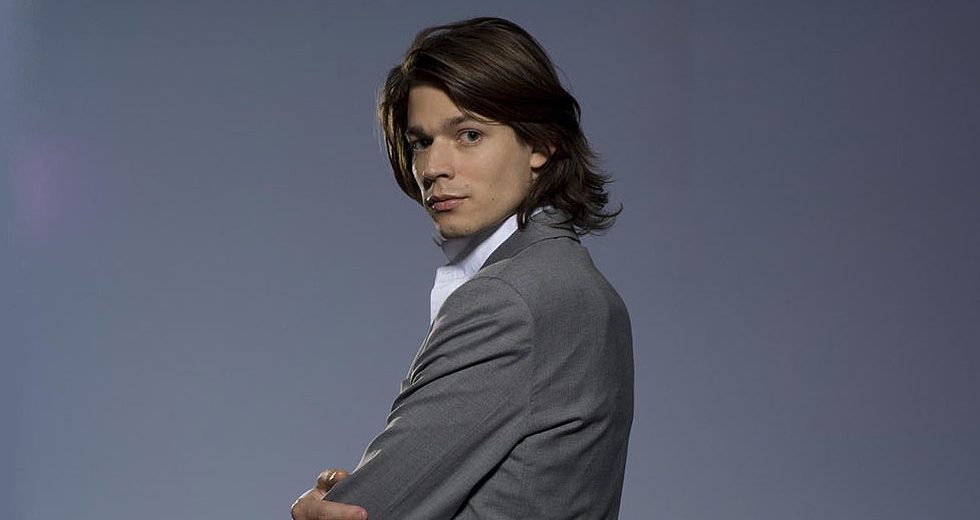

Most competition participants are driven to win. But French pianist David Fray was relieved he “only” took second place at the 2004 Montreal International Music Competition, because he didn’t have all the pressure and expectations that would have come with the grand prize.

“It was a very nice moment,” he said. “I never thought I would say that about a piano competition, because I usually don’t like them, and I did very few. But this one had a very good atmosphere. The piano technical part was not the only the thing that the judges appreciated.”

Even by winning second place, the attention that Fray, now 36, did garner in that major competition was enough to gain him an agent and a recording contract: two key ingredients that helped him go on to build a flourishing international career.

He first performed with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 2013, and he will return Feb. 22-24 and 27 as soloist in Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2. On the podium will be guest conductor Christoph Eschenbach, music director of the Ravinia Festival from 1994 through 2005. (Fray returns next season, performing Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 under Riccardo Muti on Oct. 4-5 and Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24, again with Muti, at the gala Symphony Ball on Oct. 6.)

Fray, who was born in Tarbes, near the Pyrenees, is among a bevy of talented French pianists in recent years, including Lucas Debargue, Lise de la Salle and Cédric Tiberghien. Fray believes that one reason for this surge is the quality of the training at the Conservatoire National Supérieur in Paris, where he studied with Jacques Rouvier.

“I think that good pianists and good musicians — and we don’t say it enough, by the way — come from good teachers and good schools,” he said. “I can say, at least for me, my musical education at the Conservatoire in Paris was very high-level. Then, of course, you have to develop yourself with your own personality to become an artist. But if you have a good musical grounding and a good musical education, that’s fundamental. Everything is possible then.”

Like a few other pianists, including, most famously, Glenn Gould, Fray prefers to play the piano seated on a chair, instead of the usual bench. He typically practiced at home using a chair, and a certain point, he asked himself: Why should I switch to a bench onstage just to conform to tradition? “It’s just a matter of my own comfort and my own position, which is maybe a bit unusual,” he said. “That is the thing that worked better for me.”

French pianists are often pigeonholed as interpreters of their country’s music, but Fray has largely eschewed Gallic composers and put much of his much of focus on the Austro-Germanic repertoire, including works by Beethoven, Mozart, Mendelssohn and Schubert.

One of the most important composers to Fray has been J.S. Bach. His first compact disc on the Erato label featured a pairing of works by Bach and modernist French composer Pierre Boulez (the CSO’s emeritus conductor, who died in 2016). Based on that release, BBC Music Magazine named the pianist Newcomer of the Year in 2008. “Fray’s debut is marked by an imaginative collation, Bach and Boulez, played with vibrant imagination,” its reviewer wrote. “He pushes the boundaries but resists the merely quirky. Impeccable technique allows him to speak from the heart with deceptive ease.”

After Fray finished his studies, he wanted to build his professional repertoire in a systematic way, and it seemed only logical to start with Bach, “the major figure of occidental music,” he believes, and the foundation of everything that came later. Fray found Bach’s music very challenging to master as a student, so he was intent as a more mature artist to find a way that he could connect with it.

“I said, now you have time to build your own conception of this music and find a solution that appears to be good to your ears, your taste and your style,” Fray said. “I will always remember that this was an important part of my life when I studied the Fourth Partita of Bach, the D major, and something was revealed through this work. I didn’t say that I had found all the solutions and I was completely satisfied, but maybe at this time, I started to understand what kind of musician I wanted to be and how to build a convincing interpretation of this major composer.”

Exploring rubato — Bach does not have to be metronomic, Fray contends — and tonal colors, the pianist sought to find an approach to the composer that reached the core of the music and transcended faddish interpretations. “For me, Bach is the intemporal composer,” he said. “You have to find something that makes him not Baroque, not romantic but just universal. And that’s very difficult.”