Forty-one years ago, “Star Wars” hit the theaters, and since then, movies and the film industry have never been the same. In his 1999 Great Movies essay, film critic Roger Ebert observed that “Star Wars” (1977) “melded a new generation of special effects with the high-energy action picture.” George Lucas’ space odyssey so broke the Hollywood mold that “in one way or another all the big studios have been trying to make another ‘Star Wars’ ever since.”

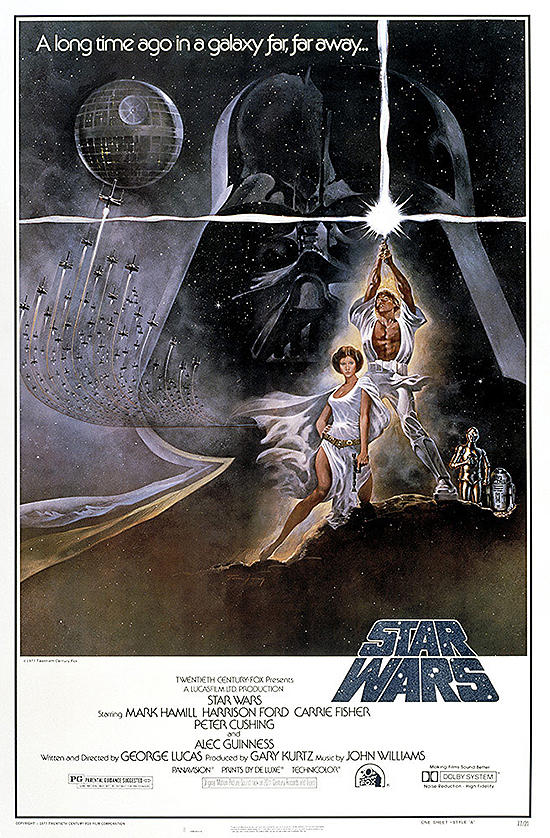

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, under guest conductor Richard Kaufman, will perform John Williams’ complete score of “Star Wars,” as the film is projected on a giant screen above the stage, in four concerts June 27-30. When Ebert wrote the following essay, “Star Wars: Episode IV — A New Hope” had been re-released in a special edition to cinemas worldwide. Since that time, the Force has remained with the franchise, with three prequels, two sequels and now a new anthology (“Solo: A Star Wars Story”) blasting off into cinema space.

BY ROGER EBERT

To see “Star Wars” again is to revisit a place in the mind. George Lucas’ space epic has colonized our imaginations, and it is hard to stand back and see it simply as a motion picture, because it has so completely become part of our memories. It’s as goofy as a children’s tale, as shallow as an old Saturday afternoon serial, as corny as Kansas in August — and a masterpiece. Those who analyze its philosophy do so, I imagine, with a smile in their minds. May the Force be with them.

Like “Birth of a Nation” and “Citizen Kane,” “Star Wars” was a technical watershed that influenced many of the movies that came after. These films have little in common, except for the way they came along at a crucial moment in cinema history, when new methods were ripe for synthesis. “Birth of a Nation” (1915) brought together the developing language of shots and editing. “Citizen Kane” (1941) married special effects, advanced sound, a new photographic style and a freedom from linear storytelling. “Star Wars” melded a new generation of special effects with the high-energy action picture; it linked space opera and soap opera, fairy tales and legend, and packaged them as a wild visual ride.

“Star Wars” effectively brought to an end the golden era of early 1970s personal filmmaking and focused the industry on big-budget special-effects blockbusters, blasting off a trend we are still living through. But you can’t blame it for what it did, you can only observe how well it did it. In one way or another all the big studios have been trying to make another “Star Wars” ever since (pictures like “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” “Jurassic Park” and “Independence Day” are its heirs). It located Hollywood’s center of gravity at the intellectual and emotional level of a bright teenager.

A poster for the original release of “Star Wars” (1977): the CSO will perform John Williams’ Oscar-winning score in live-to-picture concerts June 27-30.

It’s possible, however, that as we grow older we retain within the tastes of our earlier selves. How else to explain how much fun “Star Wars” is, even for those who think they don’t care for science fiction? It’s a good-hearted film in every single frame, and shining through is the gift of a man who knew how to link state-of-the-art technology with a deceptively simple, really very powerful, story. It was not by accident that George Lucas worked with Joseph Campbell, an expert on the world’s basic myths, in fashioning a screenplay that owes much to man’s oldest stories.

By now the ritual of classic film revival is well established: An older classic is brought out from the studio vaults, restored frame by frame, re-released in the best theaters and then re-launched on home video. With this “special edition” of the “Star Wars” trilogy, Lucas has gone one step beyond. His special effects were so advanced in 1977 that they spun off an industry, including his own Industrial Light & Magic Co., the computer wizards who do many of today’s best special effects.

Now Lucas has put ILM to work touching up the effects, including some that his limited 1977 budget left him unsatisfied with. Most of the changes are subtle; you’d need a side-by-side comparison to see that a new shot is a little better. There are about five minutes of new material, including a meeting between Han Solo and Jabba the Hut that was shot for the first version but not used. (We learn that Jabba is not immobile, but sloshes along in a kind of spongy undulation.) There’s also an improved look to the city of Mos Eisley (“a wretched hive of scum and villainy,” says Obi-Wan Kenobi). And the climactic battle scene against the Death Star has been rehabbed.

The improvements are well done, but they point up how well the effects were done to begin with: If the changes are not obvious, that’s because “Star Wars” got the look of the film so right in the first place. The obvious comparison is with Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” made almost 10 years earlier, in 1968, which also holds up perfectly well today. (One difference is that Kubrick went for realism, trying to imagine how his future world would really look, while Lucas cheerfully plundered the past; Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon has a gun turret with a hand-operated weapon that would be at home on a World War II bomber, but too slow to hit anything at space velocities.)

Two Lucas inspirations started the story with a tease: He set the action not in the future but “long ago,” and jumped into the middle of it with “Episode IV — A New Hope.” These seemingly innocent touches were actually rather powerful; they gave the saga the aura of an ancient tale, and an ongoing one.

As if those two shocks were not enough for the movie’s first moments, I learn from a review by Mark R. Leeper that this was the first film to pan the camera across a star field: “Space scenes had always been done with a fixed camera, and for a very good reason. It was more economical not to create a background of stars large enough to pan through.” As the camera tilts up, a vast spaceship appears from the top of the screen and moves overhead, an effect reinforced by the surround-sound. It is such a dramatic opening that it’s no wonder Lucas paid a fine and resigned from the Directors Guild rather than obey its demand that he begin with conventional opening credits.

The film has simple, well-defined characters, beginning with the robots C-3PO (fastidious, a little effete) and R2-D2 (childlike, easily hurt). The evil Empire has all but triumphed in the galaxy, but rebel forces are preparing an assault on the Death Star. Princess Leia (pert, sassy Carrie Fisher) has information pinpointing the Death Star’s vulnerable point and feeds it into R2-D2’s computer; when her ship is captured, the robots escape from the Death Star and find themselves on Luke Skywalker’s planet, where soon Luke (Mark Hamill as an idealistic youngster) meets the wise, old, mysterious Kenobi (Alec Guinness) and they hire the free-lance space jockey Han Solo (Harrison Ford, already laconic) to carry them to Leia’s rescue.

The story is advanced with spectacularly effective art design, set decoration and effects. Although the scene in the intergalactic bar is famous for its menagerie of alien drunks, there is another scene — when the two robots are thrown into a hold with other used droids — which equally fills the screen with fascinating throwaway details. And a scene in the Death Star’s garbage bin (inhabited by a snake with a head curiously shaped like E.T.’s) also is well done.

Many of the planetscapes are startlingly beautiful and owe something to fantasy artist Chesley Bonestell’s imaginary drawings of other worlds. The final assault on the Death Star, when the fighter rockets speed between parallel walls, is a nod in the direction of “2001,” with its light trip into another dimension: Kubrick showed, and Lucas learned, how to make the audience feel it is hurtling headlong through space.

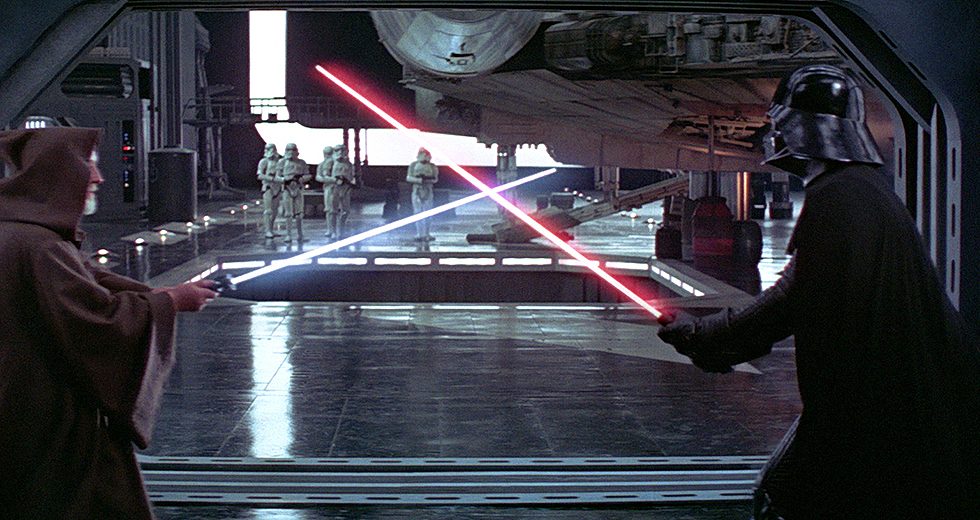

Lucas fills his screen with loving touches. There are little alien rats hopping around the desert, and a chess game played with living creatures. Luke’s weather-worn “Speeder” vehicle, which hovers over the sand, reminds me uncannily of a 1965 Mustang. And consider the details creating the presence, look and sound of Darth Vader, whose fanged face mask, black cape and hollow breathing are the setting for James Earl Jones’ cold voice of doom.

Seeing the film the first time, I was swept away and have remained swept ever since. Seeing this restored version, I tried to be more objective and noted that the gun battles on board the spaceships go on a bit too long; it is remarkable that the Empire marksmen never hit anyone important, and the fighter raid on the enemy ship now plays like the computer games it predicted. I wonder, too, if Lucas could have come up with a more challenging philosophy behind the Force. As Kenobi explains it, it’s basically just going with the flow. What if Lucas had pushed a little further, to include elements of non-violence or ideas about intergalactic conservation? (It’s a great waste of resources to blow up star systems.)

The film philosophies that will live forever are the simplest-seeming ones. They may have profound depths, but their surfaces are as clear to an audience as a beloved old story. The way I know this is because the stories that seem immortal — The Odyssey, Don Quixote, David Copperfield, Huckleberry Finn — are all the same: A brave but flawed hero, a quest, colorful people and places, sidekicks, the discovery of life’s underlying truths. If I were asked to say with certainty which movies will still be widely known a century or two from now, I would list “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “The Wizard of Oz” and probably “Casablanca” … and “Star Wars,” for sure.

Reprinted with permission from the Ebert Co. Ltd.