Until recent decades, opera in Paris followed twin tracks of very different provenance and purpose. The Opéra, deriving from court entertainments and given an apparently unassailable luster by Lully, writing for Louis XIV, promoted what the French called grandes machines, a phrase probably dating from those early years when stage spectacles — floods, tempests, volcanic eruptions — were a crucial ingredient of the evening’s fun. The plots, not exactly noted for their simplicity, dealt with kings and gods, and the acting tended toward a “stand-and-deliver” style.

Against all this, the Opéra-Comique was the home, not necessarily of comedy, though this was not outlawed, but rather of real life as lived by lesser mortals, with the accent on naturalness and believability. Other organizations did appear from time to time, notably the Théâtre Lyrique in the mid-19th century, but basically the Opéra/Opéra-Comique dichotomy held firm.

The CSO presents Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande in concerts May 14, 16 and 19, and Ravel’s L’enfant et les sortilèges on May 7-9 and 15.

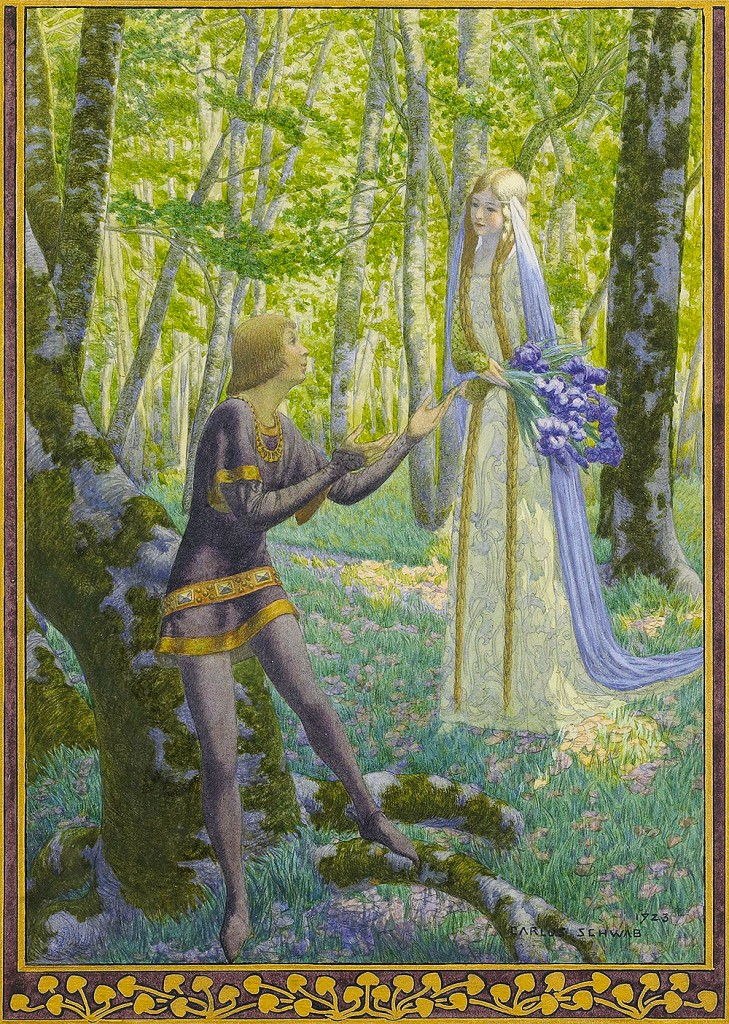

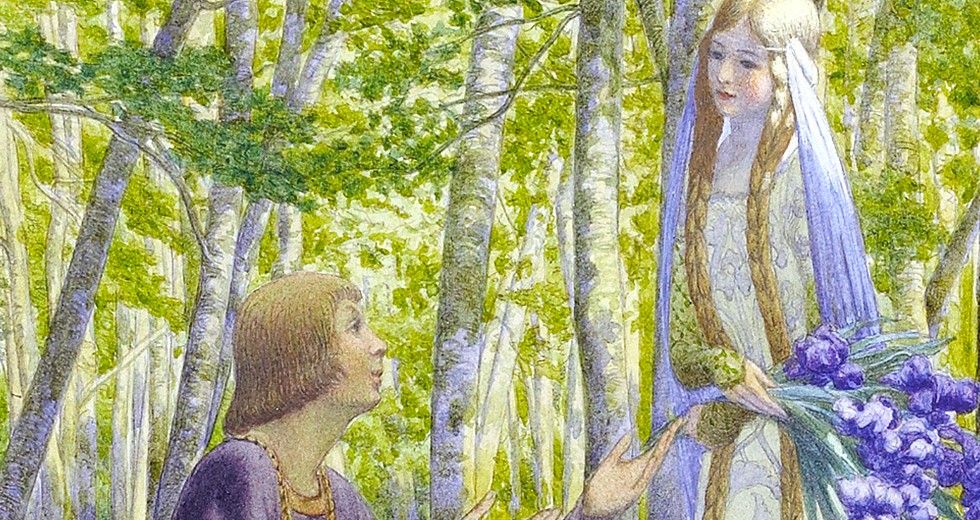

Claude Debussy’s operatic experiences in the 1890s exemplify this split with some clarity. First, he tried his hand at a grande machine on the story of El Cid, but soon realized that, as he put it, “I was winning victories over myself.” Then in May 1893, he saw Maeterlinck’s play Pelléas et Mélisande, and the grand gestures were definitively abandoned. But what to put in their place? The story most definitely does not concern the lower bourgeoisie who made up the majority of the Opéra-Comique audience: There are a king, various princes and princesses, and a castle. On the other hand, royal trappings are barely in evidence even if, as Virgil Thomson put it, the family “seems to be running some sort of kingdom.”

The one moment of regal majesty, when Golaud identifies himself as “the grandson of Arkel, king of Allemonde,” albeit underlined by Debussy with rich horns and bassoons, lasts a mere couple of bars. Instead of ceremonial, we are witnesses to a searing family tragedy that owes much to the plays of Henrik Ibsen, which were being staged in Paris as Debussy was beginning work on his score. In one of his letters, the composer mentions “la beauté du théâtre d’Ibsen,” and over the last 70 years or so, the opera has increasingly been absorbed into the “Theater of Cruelty.”

The overwhelming sentiment of the work, and one it shares with L’enfant et les sortilèges, is that of being lost — lost both physically and psychologically. This feeling is superbly evoked in the orchestral introduction. We start with two bars of modality, calling up olden times and faraway places; then, abruptly, what will soon be recognized as Golaud’s motif over the deeply unsettling harmonies of the whole-tone scale; then, most potently of all, a bar of near silence (just a faint rumble in the timpani), as if the music is shocked at what it has just done — after which we start again, shortly to find Golaud lost in the forest. The feeling of being perdu is imprinted indelibly in our hearts. So also at the start of L’enfant, the two oboes wander aimlessly around for what seems an age before the child gives voice to his boredom and repressed rage. He too is “lost,” in the sense of being without purpose.

Further evidence of his “lostness” comes in the two chords accompanying the key word “Maman!” set to Ravel’s favorite descending fourth. In the course of the opera, the second of the two chords is never given a solid bass note, as the Child continues to search for the love that can only return with (his) repentance and (his mother’s) forgiveness. Only on the very last chord does Ravel seal the pact with that missing bass note, just as the return of the wandering oboes is now anchored with beneficent G major string harmonies.

The “stand-and-deliver” method of singing referred to above, while tolerable (apparently) in operas that depended on spectacle, big tunes and solid orchestrations, was clearly inappropriate to this new kind of “inward” theater, and we can sympathize with Debussy when at a rehearsal, he enjoined the cast to “forget you are singers!” (“oubliez que vous êtes chanteurs!”). Even if this did not go down well initially, step by step the singers got the message, and contrary to what Saint-Saëns claimed was the case in all opera, they realized that Debussy’s orchestration allowed the words to be heard. Not that this was entirely new.

The great French conductor Georges Prêtre has emphasized the subtlety and efficacy of Massenet’s word setting, and that composer’s influence can be heard in both these operas: in Pelléas, at the opening of the Act 4 love duet, “On dirait que ta voix,” which is where Debussy began work, and in L’enfant in the boy’s solo “Toi, le coeur de la rose,” which Ravel admitted he took as its model Des Grieux’s aria “Adieu, ma petite table” from Manon.

We know that Ravel attended many of the 14 performances of the initial run of Pelléas in the early summer of 1902 (not all, as has been sometimes claimed, since he had a small matter of a Prix de Rome cantata to write in the middle of the run); Debussy’s way with the French language had a lasting effect on him.

Vincent d’Indy, in a highly perspicacious review of the premiere, suggested links with Monteverdi’s word setting, though one wonders what Monteverdi that Debussy knew. At all events, Debussy’s practice took its lead from the inflections of the spoken language, and, a few years later, Ravel took this idea and ran with it in his song cycle Histoires naturelles, to the extent of sometimes ignoring the mute “e” at the ends of words that, according to all the rules, had to be enunciated separately when sung. In the ensuing furor (a modern tabloid headline might read “Young Composer Punches Face of Establishment”), no one pointed out that, very occasionally and for artistic reasons, Debussy had done the same in Pelléas. In the first scene, Mélisande admits she has run away (“je me suis enfuie”) with the final “e” of “enfuie” in place.

Golaud picks up on the phrase, but now “enfui(e)” is shorn of its final “e.” Why? Because this is the first, tiny hint of that impatience and uncertain temper which will so radically determine the course of events. It might have caused Ravel some wry amusement to note that, by the time of the premiere of L’enfant in 1926, possibly as a result of the democratization of society that a world war brings, the sense of social outrage had died off, so he was able, like Debussy, to vary this technique in accordance with the dramatic situation. Whereas, in the Child’s opening outburst of fury, he is made to exclaim “je n’aim(e) personn(e),” with vigorous enunciation of the “m” and “nn,” in his lyrical duet with the Princess and the following “Toi, le coeur” every mute “e” is in place.

Inevitably, two such groundbreaking works have had their detractors. Some way through a performance of Pelléas, Richard Strauss muttered to his companion, “Is it all like this?” and complained that it lacked what he called “Schwung” (“verve,” “zest”; what we might term “zip”). Then, during the 1930s, the opera fell out of fashion, to the extent that the English musicologist Edward J. Dent could write in 1940 that “the strain of listening to this rather long opera … never knowing what the harmonies of the music are, never knowing what the characters are really supposed to be thinking and doing … is to some people unbearable.”

As to L’enfant, Ravel knew that his use of multiple numbers, as in an American musical, would cause upset in some quarters, but perhaps even he was surprised that at no single performance in his lifetime was he allowed, in Paris anyway, to hear the Cats’ Duet without audience participation.

Whether either of these two operas bears a message continues to excite opinions. That of Pelléas would seem, from the verbal text alone, to be bleak. The last words of the opera, “Now it’s the turn of the poor baby girl,” suggest, in the word “pauvre,” that maybe Mélisande’s character will find an echo in her daughter, and given that (Virgil Thomson again) “a lonely girl with a floating libido and no malice toward anyone can cause lots of trouble in a well-organized family,” you will be lost in the forest at your peril. But does Debussy’s final major triad offer hope?

The message of L’enfant is altogether more comforting. We know that forgiveness was in Ravel’s mind at the time of writing the opera, since he made clear that his visit to Vienna in 1920 was intended to help heal the wounds of the war. Maybe the opera also was meant to beg his late mother’s forgiveness for abandoning her in 1916 for the front, and possibly, thereby hastening her death in January 1917? One can only speculate.

But happily we have now gone well beyond worrying about mute “e’s,” the lack of “Schwung,” the obscure motives and the all-too-realistic cats, and can abandon ourselves to the enjoyment of two supreme masterpieces.

Roger Nichols is a writer specializing in French music from Berlioz to the present day. After working in various British universities, during which time he wrote the first book in English on the music of Messiaen, he became a freelance lecturer, pianist, translator and reviewer. In 2007, he was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur for his services to French culture. His biography of Ravel was published by Yale University Press in 2011.

© 2015 Roger Nichols