Cynthia Yeh doesn’t like to talk about career aspirations. “My personality is that I don’t think a lot about all the what-ifs and what-could-bes,” she said. “I just do and then respond to doing.” Considering Yeh was appointed principal percussionist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 2007 at age 29 and has led the section since, the no-nonsense musician has already done a great deal.

Yeh will step from the rear of the orchestra, where the percussion section is typically situated, when she serves as soloist in CSO performances Dec. 18-20 of Veni, Veni, Emmanuel, a 1992 percussion concerto by Scottish composer James MacMillan. She performed the work in September with the Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional in Mexico City, where Carlos Miguel Prieto, the guest conductor for these concerts, has served as music director since 2007.

As principal percussionist, Cynthia Yeh creates an assignment spreadsheet that lists which percussionist will play what instrument in each piece.

The percussionist’s quick ascent to the top of the symphonic world is particularly impressive, given that she was planning a career in business when she enrolled at the University of British Columbia. But a little background first. Yeh was born in Taipei, Taiwan, and moved with her family to Vancouver, B.C., when she was 10. Yeh had started piano lessons at 4, and she continued those studies in her new home. When she was old enough, she wanted to play in the school band. Because there was no slot for a pianist, the band leader made her a xylophonist, to take advantage of her ability to read music, a skill that many of the other young percussionists did not possess. “For the heck of it,” as she put it, Yeh also learned how to play the snare drum and drum set on the side. “I was back there all through high school winging it, because it was so easy,” she said.

When she began college, Yeh never gave any thought to a career in music. But about halfway into her freshman year, she switched gears and decided to give music performance a shot, studying under the piano teacher with whom she had already been taking lessons for more than six years. “During that time, I thought I would sign up for percussion ensemble,” she said. “Because it was so easy in high school, I thought that would be a really easy credit.” The class turned out to be anything but easy, but she became so enamored with her percussion studies that she started neglecting the piano. So it did not come as a surprise when her piano teacher told her that she had to make a decision between piano and percussion. “And I said, ‘Fine, I quit,’ ” she recalled. “So I quit piano. No one thought that I was serious.” But she was.

After graduating with a music performance degree in 1999, Yeh vowed to pursue a music career until she was 30. If she hadn’t succeeded at finding sustainable employment by then, she would return to her original plan of going into business. “But then, I will have at least given music a try,” she recalled. But as subsequent events have made clear, she needn’t have worried.

Yeh went on to earn her master of music performance degree from Temple University in Philadelphia in 2001 and freelanced for several years in orchestras along the East Coast from Springfield, Mass., to Richmond, Va. In 2004, she landed the position of principal percussionist with the San Diego Symphony, and just three years later, Yeh auditioned with the Chicago Symphony and won her current post. “This was actually my dream job, but I didn’t think it would ever come open,” she said. But it so happened that her predecessor, Ted Atkatz, unexpectedly left in 2006 to perform with NYCO, an alternative rock band. “It’s an amazing place to work,” Yeh said. “It’s an amazing place to play, especially on tours, when you’re just together all the time, playing concert after concert. The stuff that comes out from our colleagues — some of it is just amazing and you’re inspired by it all the time. And the conductors we get to see and work with are incredible.”

Yeh is a little bit of an outlier in her family, because no one else is musical. “My mom was tone-deaf and rhythm-deaf,” she said. “She couldn’t clap to a beat and she couldn’t match a pitch. Forget it.” The family joke is that her parents took the wrong baby home from the nursery. Even now, she remains a bit of a mystery to her relatives. “Because I don’t come from a family of musicians,” she said, “no one understands what I do.”

When the CSO visited Taipei in January 2013, Yeh had a chance to return to her birthplace. Because the works scheduled for the two concerts in the city called for almost no percussion, she “embarrassingly” got to perform only during one of the encores. But as one of the two Taiwanese natives in the CSO (concertmaster Robert Chen is the other), she was nonetheless called on to participate in a few press events during the visit.

A percussionist is expected to know how to play all the dozens of different instruments — everything from cowbells to vibraphones — designated in the scores of compositions that the CSO tackles each season. “I love playing great bass-drum parts. Love playing good snare-drum parts. In the orchestra, I like playing everything. The only thing I like to avoid is playing the chimes, because I’m short,” said Yeh, who stands at 5 feet, 1 inch.

Yeh is not big on naming favorites, but confessed that “it’s a lot of fun to play Shostakovich. It’s fun for me to play Mahler bass-drum parts, because he writes great bass-drum parts. Obviously, the Verdi Requiem is really fun to play. There’s a lot of great stuff we get to play, so I can’t pinpoint that many.”

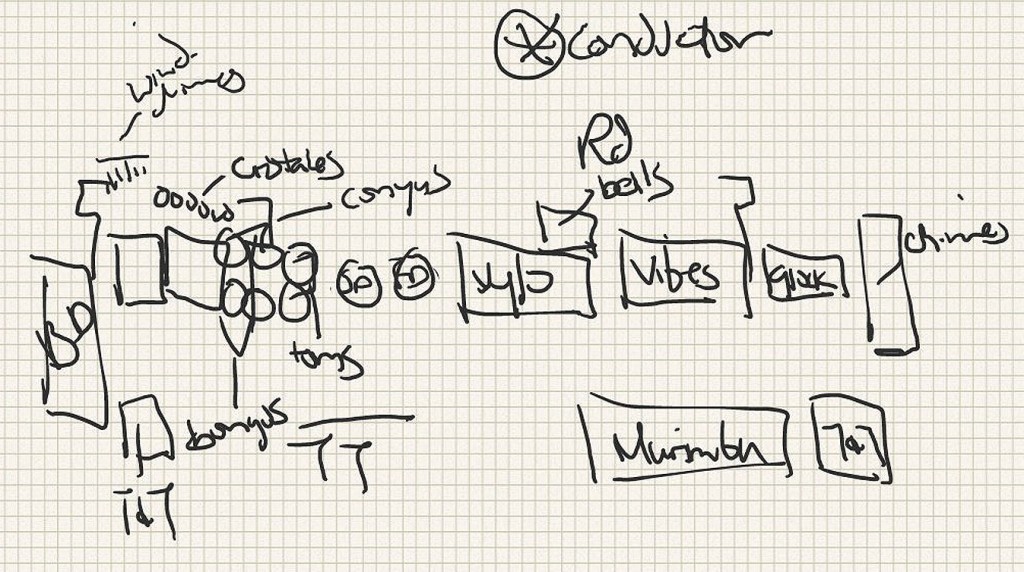

For each work, Cynthia Yeh draws diagrams to indicate where all of the percussion instruments should be placed. This diagram shows the set-up for the “Pixar in Concert” programs last month.

Principal percussionist is one of an orchestra’s most demanding leadership positions. Unlike other sections, where scores spell out which groups of musicians play what notes, Yeh is responsible for determining which percussionists will play the specified instruments in any given piece — a task she must complete several months before each season begins. “A lot of the rep has a clear principal part, so if it’s like the snare-drum part in [Ravel’s] Bolero, obviously I would play it. You’re expected to play that.” A range of other considerations figure in as well, including her preferences and tradition. For instance, if a player’s predecessor in the percussion section regularly played a certain part, then he or she often inherits that role.

Along with figuring out who plays what part, she also has to decide how the percussion instruments will be arranged onstage to facilitate minimal shifting and easy sharing. In dome orchestras, percussion players can be seen running from one instrument to the next with sheet music in their hands. “I try to really, really hard not do that,” Yeh said. Before each program, she gives the CSO’s stagehands fastidious hand-drawn diagrams that lay out where all of the percussion instruments should be placed.

When she takes the stage Dec. 18-20, it will mark just her second time performing as a soloist with the CSO. MacMillan’s concerto is written in one continuous movement and lasts about 25 minutes, and according to his notes on the piece, the “soloist and orchestra converse throughout as two equal partners.” The work is based on a familiar 15th-century French Advent plainchant, which was later paired with a historical text that is known in English as O come, O come, Emmanuel.

MacMillan indicates that the concerto is a purely abstract work on one level, but on another, it can be understood as a musical exploration of the theology behind the Advent message. “The heartbeats which permeate the whole piece,” he writes, “offer a clue to the wider spiritual priorities behind the work, representing the human presence of Christ. Advent texts proclaim the promised day of liberation from fear, anguish and oppression, and this work is an attempt to mirror this in music.”

Yeh estimates that she plays at least 25 different instruments in the piece, including marimba, log drum, congas and gongs. “I think it is a really interesting piece,” she said, “in that there is enough variety so that it’s not just all marimba or all drums or all loud.”

Kyle MacMillan, former classical music of the Denver Post, is a Chicago-based arts writer.

TOP: Cynthia Yeh prepares for a rehearsal at Vienna’s Musikverein during the CSO’s European Tour this fall. | Todd Rosenberg Photography