The CSO doesn’t readily bestow the title of principal guest conductor. In the orchestra’s long history, only three conductors have held the post: Carlo Maria Giulini from 1969 to 1972, Claudio Abbado from 1982 to 1985, and most recently, Pierre Boulez. A composer as well as a conductor, Boulez was the CSO’s principal guest conductor from 1995 to 2006, when he became conductor emeritus, a post he held until his death in January 2016 at age 90.

All principal guest conductors have a special relationship with the orchestras they serve, but Boulez’s ties to the CSO ran especially deep. He was a close friend and colleague of Daniel Barenboim, CSO music director from 1991 to 2006, who invited Boulez for annual residencies starting in 1991. After Barenboim’s departure, frequent residences with Boulez and another distinguished maestro, Bernard Haitink, helped keep the orchestra on an even keel until Riccardo Muti arrived as the CSO’s 10th music director in 2010.

MusicNOW, the CSO’s contemporary chamber music series, will honor Boulez at its concert titled “Illuminating Boulez” on April 3 at the Harris Theater. The program features three works by Boulez, including Dérive 1, composed in 1984, and 12 Notations, a set of solo piano pieces from 1945 that Boulez transcribed over the years for assorted ensembles. Also, Mémoriale, the middle section of a 1972 piece reworked by Boulez into an arrangement for solo flute and eight instruments in 1986. The program also includes the world premieres of two CSO commissions: shadows of listening by Marcos Balter and For Two or Three Instruments by Pauline Oliveros.

Pierre Boulez and Daniel Barenboim (at the piano) rehearse with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in February 1969. | Photo: Terry’s

Boulez made his CSO debut in 1969. Just as countless audience members appreciated the translucent colors and elegant expressiveness of Boulez’s CSO performances, many current orchestra members have happy memories of his decades in Chicago.

John Bruce Yeh, assistant principal clarinet who joined the CSO at age 19 in 1977, was soloist in the CSO’s performances of Elliott Carter’s Clarinet Concerto, conducted by Boulez in 1998.

“Boulez was so organized,” Yeh said. “He was the most organized conductor we’ve ever had in terms of being able to take very complex music apart, fix everything and put it back together and make it sound just right. It was astounding to watch. Arnold Schoenberg’s Pelleas und Melisande, for example. It’s a very thickly orchestrated piece, and he knew exactly how to bring out the important voices and subdue everything else.”

Michael Henoch, assistant principal oboe who joined the CSO in 1972, recalls attending Boulez’s CSO debut in 1969. “As a student, I attended the concert, his very first with the Chicago Symphony, and the piano soloist was none other than Daniel Barenboim in the Bartok First Piano Concerto. There was such demand for that concert that I had an awful seat, second row of the main floor. But I was really up close, and it made a big impression on me.

“As a student at Northwestern, we heard so much about Pierre Boulez as this great composer and an admired conductor. He did Jeux by Debussy and Messiaen’s Et exspecto resurrectionen mortuorum. [The concert also featured two works by Anton Webern: Passacaglia and Six Pieces for Orchestra.] Everything was so clear, so well-balanced and clean. That music is incredibly difficult, and it just sounded perfect.”

An astute music scholar as well as ground-breaking composer, Boulez was a firebrand in his youth, issuing polemical broadsides about the state of the musical world after World War II. In the 1960s and 1970s as guest conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra and music director of the New York Philharmonic, he earned the nickname “The French Correction” for his uncanny ability to hear the slightest smudge in orchestral texture.

By the time Boulez returned to the CSO in 1987 after a 19-year hiatus, Henoch had 15 CSO seasons behind him. But he was apprehensive about performing under Boulez’s direction. “Frankly, I was a little nervous,” Henoch said. “His reputation was such that he heard everything, he cleaned up everything. I just wanted to be the best prepared I could possibly be.”

Celebrating his 70th birthday in 1995, Pierre Boulez and Daniel Barenboim acknowledge applause following a performance of Bartók’s First Piano Concerto on April 1. | Photo: Cheri Eisenberg

Boulez’s artistic standards were as lofty as ever when he became a regular CSO visitor in the 1990s. “I loved playing for him because of his knowledge, the clarity of his gestures,” Henoch said. “There was never a false move. I don’t remember him ever making a mistake. Everything was done to the highest standards, to the first order of excellence. No matter what he conducted, he was going to do the best he could and get the best out of everyone.”

But as Boulez settled into his 60s, his manner had mellowed. “When he made a correction, he didn’t get personal about it,” Henoch said. “He never scolded you. He was never condescending, never mean. He was patient. He knew that many times what we were doing was actually more difficult than what he was doing. He would make gestures, but between the gestures, we would be playing 10,000 notes.

“I don’t ever remember him losing his temper, and this is very unusual in our world. He was demanding, but he was fair. He knew he was conducting a great orchestra, a very well-prepared orchestra. He knew he was working with human beings who were giving their best.”

Baird Dodge, principal second violin, joined the CSO in 1996 and has vivid memories of rehearsals for one of the orchestra’s most ambitious undertakings, performances of Schoenberg’s fiendishly difficult opera, Moses und Aron. In 1999, the orchestra performed the work in Chicago and on tour in Berlin.

“Boulez thought this was important to do, regardless of how it might be received by some audiences,” Dodge said. “He was so capable and experienced and brilliant that he knew it would be difficult for us, and so he was, in a way, remarkably patient. That’s not what you expect from someone who is so brilliant.”

The clarity and elegance of Boulez’s performances prompted some to dismiss his approach as too cool and analytical. But Dodge recalled his emphasis on what he calls “old-fashioned, beautiful playing.”

“No matter what the repertoire, there was a naturalness to the gesture, and the rhythm was always human,” Dodge said. “It was never like a computer. It always had an ebb and flow, a sense of breath.”

Wynne Delacoma, classical music critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1991 to 2006, is a Chicago-based arts journalist and lecturer.

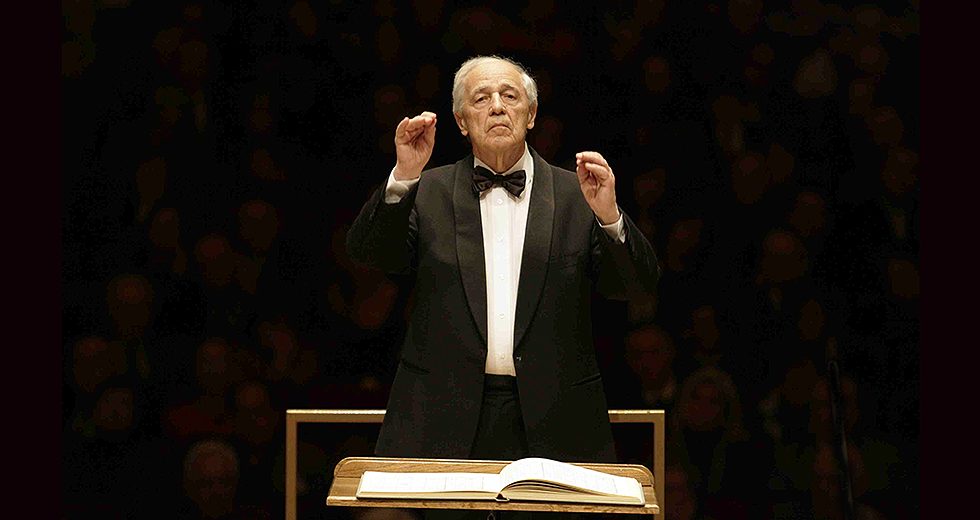

TOP: Pierre Boulez leads the CSO during a tour performance at Carnegie Hall in December 2006. | Todd Rosenberg Photography