The first time Richard Kaufman met film composer John Williams, the former was playing violin as the latter conducted during a recording session for Steven Spielberg’s film “Jaws” (1975).

Kaufman was already a fan of the soon-to-be-famous Williams, having enjoyed his soundtrack work for “Goodbye, Mr. Chips” (1969), a flop musical remake of the 1939 film. When he told Williams as much, the maestro looked at him as if to say, “Oh, are you the one that saw it?”

And so began a decades-long professional relationship during which Kaufman would play on several more Williams soundtracks, including the one for Spielberg’s blockbuster “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (1977).

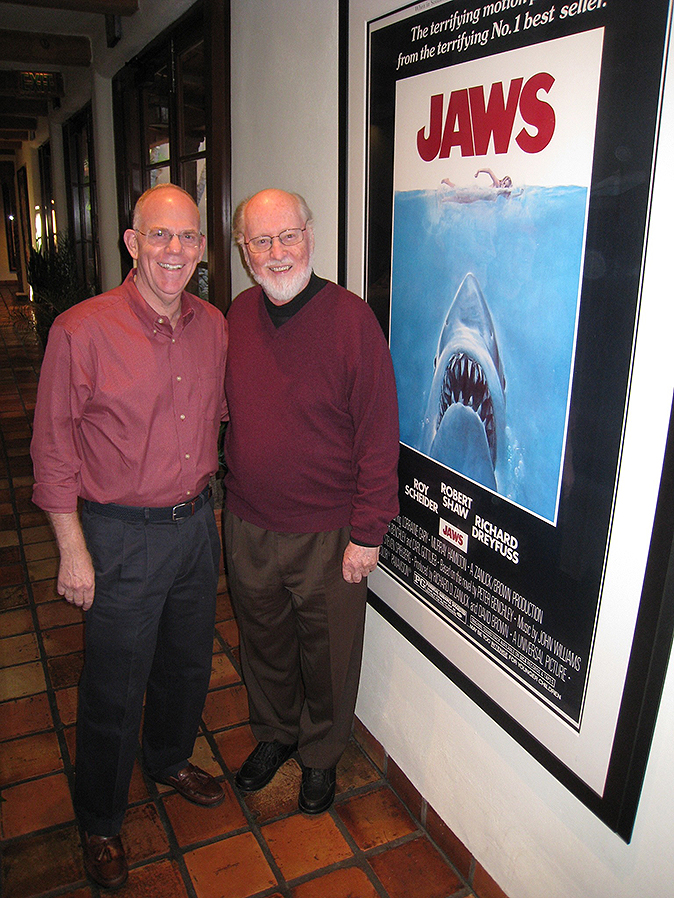

Richard Kaufman (left) and John Williams first worked together on the recording of the “Jaws” soundtrack.

More recently, Kaufman has toured the country conducting Williams’ music for George Lucas’ “Star Wars” films. The two shared podium duties in Chicago last spring when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra performed a program of Williams’ movie music, featuring many of the scores that won the composer five Oscars (and 51 nominations). Two months later, Kaufman returned to Symphony Center to conduct Williams’ soundtrack from “Star Wars: Episode IV — A New Hope” (1977) while the movie was projected on a screen overhead.

He’ll do likewise when the CSO presents live-to-picture performances Nov. 23-25 of Williams’ score for “The Empire Strikes Back” (1980). Two more films in the “Star Wars” series, including “Return of the Jedi,” are slated for similar treatment in the near future.

Asked what makes Williams’ film scores stand out, Kaufman prefaces his reply with insight from another Oscar-winning composer, Elmer Bernstein of “The Magnificent Seven” (1960) and “Ghostbusters” (1984) renown. More than a writer of great melodies and orchestration, Bernstein believed a successful film composer must be a top-notch dramatist who can watch a scoreless film and determine where the music should and shouldn’t go.

Williams, Kaufman says, is a master of that. “John really appreciates great storytelling, and the music he writes truly accompanies the story and only calls attention to itself when he means for it to call attention to itself.”

Since Williams’ music is so “emotionally accessible,” Kaufman is hopeful that those who come to hear it live and have never been in a concert hall will be inspired by the experience and return for more typical orchestral fare.

Apart from the music, on a more logistical front, the process of synching soundtrack and visuals in a live setting is no easy feat. Even more challenging, Kaufman says, are the extended lulls. Unlike a typical symphony, during which an orchestra might have several bars’ rest, film scores call for musicians to stop playing for minutes at a time.

“It’s [a matter] of keeping the orchestra involved in terms of getting them to the highest level of energy very quickly after they’ve been sitting,” Kaufman says. “But when you have an orchestra like Chicago’s, whose players have a dedication and a commitment to excellence, you don’t have to do a lot to get the them to be brilliant.”

But it’s a different breed of brilliant than goes into playing, say, a gorgeous Mozart or Beethoven symphony. “In film,” Kaufman says, “the music really becomes a character, and the orchestra, in a sense, become musical actors. In the case of a lot of orchestras, and certainly with the Chicago Symphony, they embrace this. And most of them, as they’ve expressed to me, really enjoy it.

“They really understand that the music is an important and integral part of the experience the audience will have.”

Mike Thomas, a Chicago-based writer, is the author of the books You Might Remember Me: The Life and Times of Phil Hartman and Second City Unscripted: Revolution and Revelation at the World-Famous Comedy Theater.

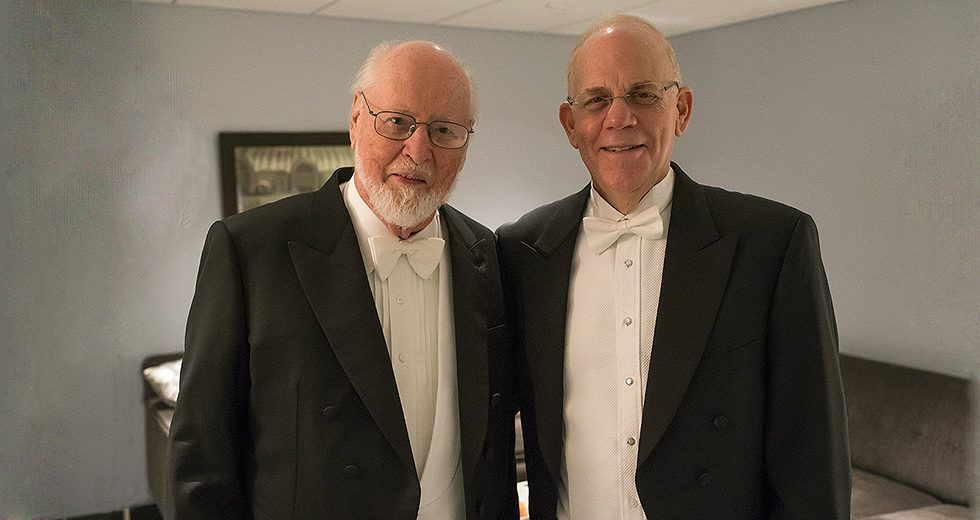

TOP: John Williams (left) and Richard Kaufman pause for a photograph backstage after their CSO concert together on April 26. | ©Todd Rosenberg Photography 2018