In November, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra launched the 10th season of its imaginative Beyond the Score series with a program honoring the 90th birthday of composer Pierre Boulez. Titled “A Pierre Dream,” it was one of the most complex productions ever devised by Gerard McBurney, creative director of Beyond the Score. Working with video artists and architect Frank Gehry, McBurney came up with a program full of almost hallucinatory images and sounds that eloquently explored Boulez’s life and his color-saturated, crystalline music.

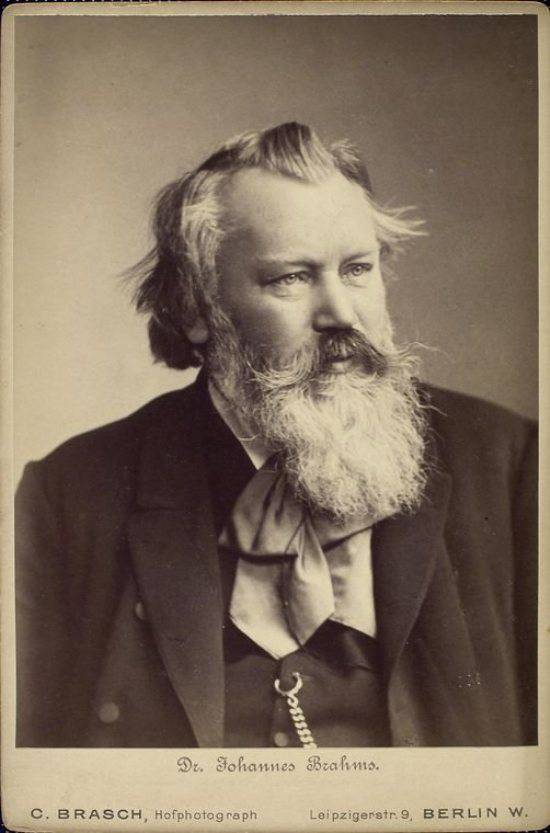

After “A Pierre Dream,” it might seem that the next Beyond the Score program (7:30 p.m. March 27 and 3 p.m. March 29) focusing on Brahms’ Third Symphony would be a walk in the Prater. Brahms, after all, is one of classical music’s most popular composers, occupying a permanent spot in the classical music pantheon, along with Bach and Beethoven, a member of the legendary Three Bs. His symphonies, concertos and chamber music are staples of the repertoire, and countless articles, academic papers and books have been written about his life and work. Brahms would seem to be an ideal composer for Beyond the Score’s typical mix of theater and musical excerpts.

Not exactly, according to McBurney.

“Brahms is a really, really tough subject for Beyond the Score,” he said. “What we have with Brahms is a composer who insisted on the purity and autonomy of the art form. He was uninterested in the biographical; he was uninterested in the idea that music might depict something outside itself. In fact, we know he wasn’t really uninterested in that, but he was very, very defensive about it.”

The irony is that Brahms, born in 1833 and died in 1897, lived during the height of the Romantic era, when composers were pouring the details of their lives onto score paper, and audiences craved a deep emotional attachment to the music they heard at concerts and played at home. Mendelssohn and Liszt chronicled their travels in orchestral and piano pieces. Titles like Pathetique, Eroica and Moonlight became permanently attached to symphonic pieces, concertos and piano sonatas. It was not the best of times to argue that a piece of music exists simply as itself rather than reflecting an individual human experience.

And Brahms’ life was not without its drama. A lifelong bachelor, was he or wasn’t he deeply in love with Clara Schumann, one of the era’s virtuoso pianists and devoted wife of composer Robert Schumann? Brahms also found himself caught up in the decades-long artistic furor revolving around Richard Wagner, that supreme master of personal and operatic drama. Wagner’s long, passionately emotional operas divided the era’s audiences, critics and academics. Many adored his experiments with endless melody and daring harmonies; others loathed them. The arguments on both sides resonated throughout 19th-century Europe’s large, opinionated artistic world. Foes of Wagner championed Brahms as the antidote to what they saw as Wagner’s self-indulgence and dangerous disregard of centuries-old musical norms.

But what Brahms really thought about all this drama swirling about him isn’t clear. “Brahms was such a private man that we don’t really know what was going on in his head most of the time,” McBurney said. “All we have to go on is the music and his sort of famous rudeness to those around him. It’s not a story that yields itself very easily to Beyond the Score.”

McBurney’s program is subtitled “Free But Happy,” referring to Brahms’ motto, Frei aber froh, inspired by a musical motif of F-A-F (which appears throughout his Third Symphony). The program will feature some of the people important in Brahms’ life, including the leading Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick, who famously denounced Wagner and championed Brahms. (Hanslick was the model for Beckmesser, the pedantic critic in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.) But the focus will be on Brahms’ music, specifically the Third Symphony, which he composed in 1883 during a summer stay at the German spa town of Wiesbaden.

“What I’ve done,” said McBurney, “is to look really, really closely at the way he manipulates the [musical] material. It’s so self-conscious. As he puts it, ‘I want the idea to be completely clear. I want the listener to hear the idea in every transposition, augmentation and inversion.’

“Well, there are an awful lot of people who go to concerts who are not interested in either transposition or augmentation or inversion,” said McBurney with a laugh. “But he was.’’

During his research, McBurney studied the state of German culture in the mid-19th century. It was a time, he said, quoting the contemporary Wagner scholar John Deathridge, when the country’s philosophers, historians and artists of all kinds, including composers, were “torn between purity and impurity.”

Europe, including Germany, was going through serious political upheaval, with revolutions, some more successful than others, repeatedly flaring up. Modern thinkers like Kant were upending philosophy. The ground seemed to be shifting, and artists of all kinds were grappling with the question of forging ahead with new ideas or clinging to older ways.

“It was part of a much bigger battle that was going on,” McBurney said. “The lines were drawn in German culture.”

Brahms’ music seems to land somewhere in the middle, according to McBurney. “As John said to me, ‘No wonder people get worried about Brahms. Brahms never says anything and provides nothing, even inside the music, to indicate what it’s about. And yet, after a performance of the Third Symphony, it’s clearly about something. What it is, we do not know. But it is about something.’ ”

Shakespeare’s quote, “What’s in a name?,” applies to Brahms’ approach to composition.

“Do we give a name to something or do we not give a name to something?” McBurney asked. “They were all obsessed with [the notion of] the ideal mental formulation. And for the purists in music — and Brahms is the supreme one — music has the capacity to present you with these ideal formulations without having to give names to them.”

This season’s trio of Beyond the Score composers — Boulez, Brahms and Ravel (coming up on June 5 and 7) — would seem to have very little in common. But McBurney has discovered an unexpected link.

“We have three very, very private men who didn’t live private lives,” he said. “They were extremely controlling as artists. All three of them are trying to make sure that every little jot and tittle in their music has some kind of cosmic significance.”

Just don’t expect Brahms to give his cosmos a name.

Wynne Delacoma, former classical music critic of the Chicago Sun-Times, is a Chicago-based arts writer and lecturer.