In 1958, when the first stereo recordings were hitting the market, RCA Victor signed the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to its newest, most prestigious imprint, Living Stereo. The series was to be a showcase for the era’s classical stars: Van Cliburn and Arthur Rubinstein, Jascha Heifetz and Gregor Piatigorsky, Jussi Björling and Leontyne Price. If the depth and clarity of stereo sound didn’t yet lure classical music lovers, the fantastical cover art may have drawn their attention.

Living Stereo capitalized on advancements in stereo disc cutters, which revolutionized vinyl production, and playback equipment, ushering in a golden age of home hi-fi systems. This past spring, Sony Classical (which now controls the RCA Victor catalog) marked the imprint’s 60th anniversary with a series of playlists — Living Stereo Spectaculars, Living Stereo Top 50, and Living Stereo Deep Cuts — on streaming platforms, including Spotify and Apple Music. The streams complement the 60-disc “Living Stereo: The Remastered Collector’s Edition Box Set,” released in late 2016.

Jay Friedman, who joined the CSO in 1962, recalls that “you could hear every voice clearly” in a Reiner disc. | ©Todd Rosenberg

CSO Principal Trombone Jay Friedman recalls that before he joined the orchestra in 1962, he “wore down the grooves” on several RCA LPs, including a collection of Richard Strauss opera scenes, conducted by the CSO’s legendary sixth music director, Fritz Reiner. “The orchestra was great at that time,” recalled Friedman, who joined the CSO during Reiner’s final year as music director. “He had a very good orchestra, and he knew it.”

Friedman believes Reiner’s exacting musicianship aligned with the sonic requirements of early stereo. “There was a certain amount of fear inherent in the job,” he said with a chuckle. “The thing with Reiner is, maybe the fear factor came into play, but the sound was always very transparent when he conducted. You could hear every voice very clearly. There was never any muddiness in his music-making.”

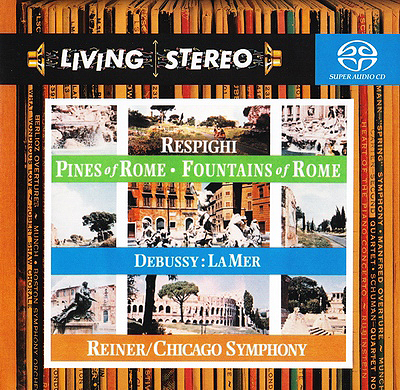

Two years before joining the CSO, Friedman was hired to play fourth trombone on a session for Respighi’s Pines of Rome, which was especially difficult to record because of its wide dynamic range. As historian Kenneth Morgan writes in his program notes for RCA’s complete Reiner set, released in 2013. “Reiner selected key passages, had them taped and then checked the balance on the playbacks to ensure that a fine recording was made.”

Another Reiner strategy was to record pieces after they were thoroughly rehearsed for subscription concerts. This permitted long takes that would give the feel of a live performance (the finale of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazade was notably recorded in a single take without edits).

In his autobiography, The Right Place, The Right Time!, former CSO Principal Flute Donald Peck describes the occasional push and pull between Reiner and RCA’s team, led by producer Richard Mohr and engineer Lewis Layton. In a 1962 session for Strauss’ Don Juan, Mohr paused to ask Reiner to re-record a short passage, claiming that an outside car horn had bled onto the tape. In fact, “it wasn’t a car horn but a cracked note from one of the French horn players that was at fault,” Peck wrote. Mohr didn’t want to embarrass the musician but Reiner would agree to redo the eight measures only after listening to the playback to identify the problem. “That is the only splice in the whole performance, which is an ecstatic one,” Peck said.

In 1960, Jay Friedman played fourth trombone on this recording of Respighi’s The Pines of Rome.

Michael Gray, an authority on historical recordings who wrote the Living Stereo liner notes for Sony, believes that Chicago’s recordings on the imprint were the most successful of any orchestra, due in part to the acoustic of Orchestra Hall at the time. The hall’s stage was wide and shallow, which enabled producers to set up three, widely spaced microphones, one for each channel.

“The left and right microphones were so far apart that you got a huge feeling of space from the sound that you didn’t get in Boston,” Gray said, referring to Boston’s Symphony Hall. The center microphone could zero in on the soloist. “In Chicago, they really had the best possible environment for making records, even records with soloists.”

Soon after Reiner retired in 1962, RCA replaced the Living Stereo imprint with Dynagroove, a lower-cost brand aimed at consumers with more modest home equipment. “The idea of Living Stereo in the beginning was that it should sound best on high-end equipment, but high-end equipment wasn’t commonly available, and the stereo records sold a lot fewer copies,” Gray said.

The CSO continued to record for RCA (and for roughly a dozen other labels, including its in-house CSO Resound); to date, its recordings have earned 62 Grammy Awards from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences.

Living Stereo could have been forgotten but in the 1980s and ’90s record collectors rediscovered the plush, balanced tones of the old LPs, now heard through superior playback devices. The imprint’s appeal widened with reissues on CD and SACD.

To Friedman, Living Stereo evokes a more freewheeling era in recording. “A lot more time was spent on recordings in the ’50s and early ’60s,” he said with a touch of wistfulness. “Companies were willing to spend the time and the money to do it.”

A New York-based writer, Brian Wise also is the producer for the CSO Radio broadcasts.