It’s obvious that to have a great orchestra you need great players and a dynamic conductor. You also need dedicated stagehands. Chairs and music stands do not magically appear; for one concert, the stage might need to be reset with different seating arrangements. A Baroque work using 20 musicians, followed by a Mahler symphony requires a major reconfiguration. And there’s sound. Microphones have to be set up for broadcasts and recordings. It’s all an unending series of detail-oriented tasks.

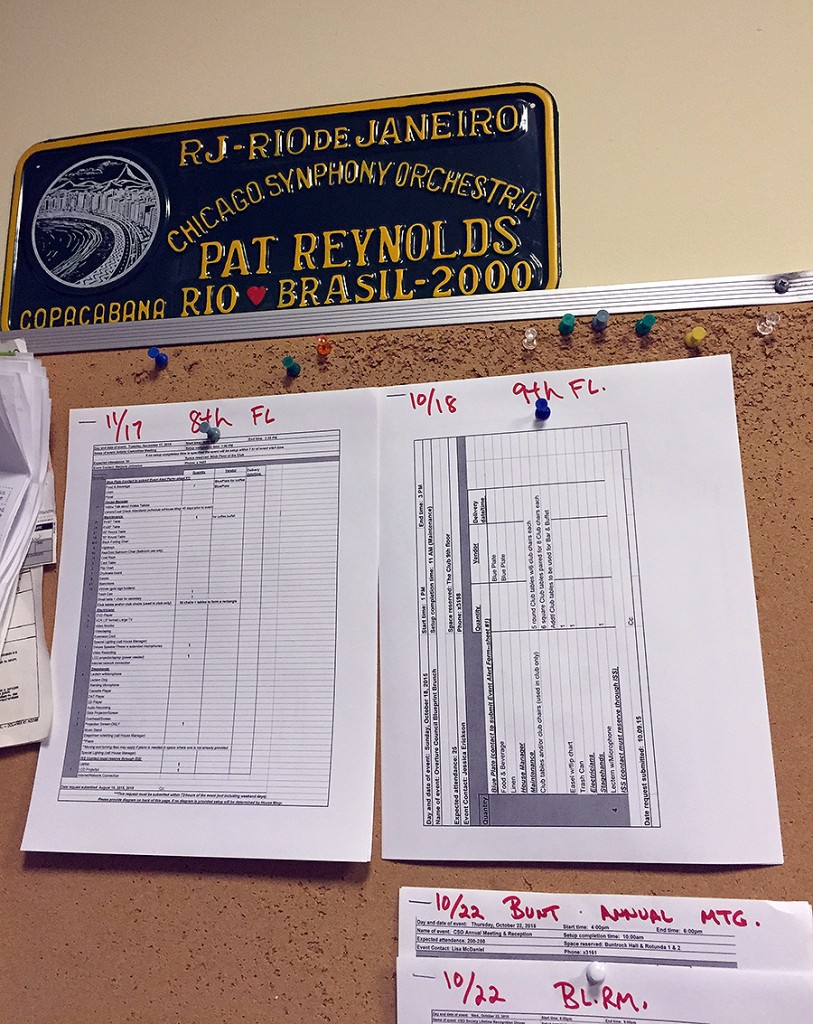

Mementos from past CSO tours decorate the walls of Reynolds’ backstage office. | Photos: Jack Zimmerman

For 30 years, stagehand Patrick Reynolds has dealt with CSO concerts, orchestra tours both near and far, and non-orchestra events such as the Symphony Center Presents Jazz Series. “It’s been a great time,” he says. “Things change from week to week, but usually we put in between 60 and 80 hours. There’s a seven-man house crew, three steady extra crew members, and we have extra people as we need them. We usually work six days a week.”

It’s a daunting schedule, but for Reynolds, there’s an end in sight. His first day of retirement will be May 1, 2016. “I used to be ‘the kid,’” Reynolds says, laughing. “Now I’m the old guy. I’ve spent 30 years of my career working here.”

Reynolds comes from a family of stagehands. “My father, his father and his father’s brother were all stagehands. And so are my two brothers, a cousin and my oldest son. My first job as a stagehand was at Mill Run Theater in Niles in 1974. I was a sound man at Arie Crown [in McCormick Place] for nine years. Then I came here.”

Reynolds is still a sound man. “We have a whole crew of guys but just three of us do sound,” he says. “We put up all the mikes for recordings and for the radio broadcasts. We have 24 mikes hanging in the air and sometimes another 24 on the stage.”

Plenty of other events require his expertise — the SCP Jazz Series for example, and there are audio needs in different parts of the building, including pre-concert lectures. Even though the orchestra performs acoustically, Reynolds is called on to mike a celeste or harp at times.

One of the difficulties Reynolds deals with is the nature of Orchestra Hall, which was designed as a purely acoustic venue. Shows, such as the jazz concerts, can be tricky to amplify. “It’s sometimes challenging, especially for the louder shows,” he says. “It’s acoustically live here — designed for the orchestra.”

Shows that do not involve the orchestra and that are heavily amplified require some extra measures. “We hang black drapes to deaden the sound of the monitors,” says Reynolds, referring to the speakers aimed at the performers so they can hear themselves. “The drapes keep the sound from bouncing back off the rear wall. Thanks to the drapes, the sound dies back there.”

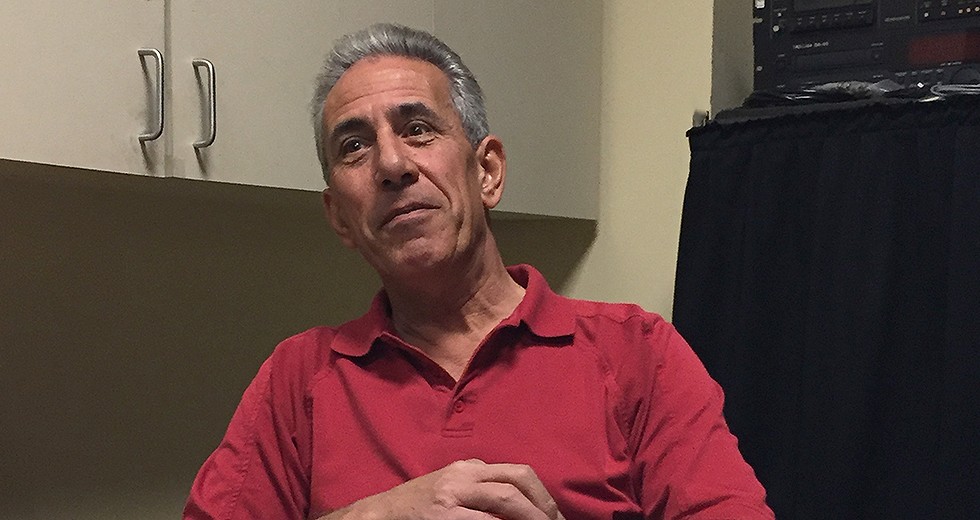

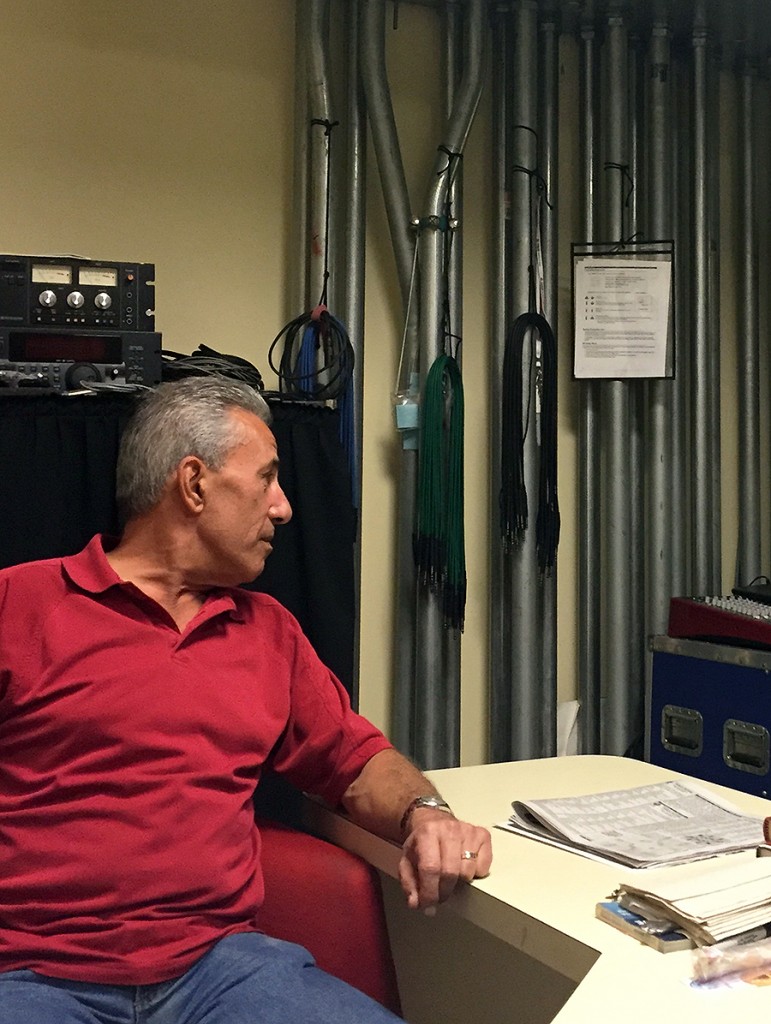

At his desk backstage in Symphony Center, Patrick Reynolds reflects: “I used to be ‘the kid.’ Now I’m the old guy. I’ve spent 30 years of my career working here.”

Though he has been exposed to a vast range of classical repertoire as part of his job, Reynolds observes that he has traditional musical tastes. “I like Mozart and Beethoven, and I’ve learned to like Mahler,” he says. “Among the new composers, I like Mason Bates and Anna Clyne [the CSO’s composers-in-residence from 2010 to 2015]. I’ve worked closely with Mason. For a couple of his world premieres, he used audio and computer-generated sound.”

Over his 30 years with the CSO, Reynolds has witnessed some major changes in the hall, especially those dealing with programming. “The jazz series didn’t start until 20 years ago. There were some pop shows and jazz-type shows but they were few and far between. These days, we normally have four rehearsals in a week, but that’s just the symphony.”

A veteran of many CSO tours, Reynolds first went on the road with Solti to the Soviet Union in 1990. “It was five days in Leningrad, five days in Moscow, a couple days in Budapest. On that tour one of the trucks got lost. We didn’t know where it was. We sat in the lobby of the theater in Moscow. It was winter, and it was cold. Somebody found a deck of cards, so the crew and Henry Fogel, [then] the president of the CSO, sat down, and we played cards until the truck finally showed up. At the time I was 36 and had never traveled to those kinds of places.

“I’ve gone everywhere with the orchestra. One time we had a load-in in Romania and had to put everything through a second-story window with a forklift because they didn’t have an elevator. In Portugal, the trucks couldn’t make it up a hill, so we had to offload everything onto smaller trucks. We travel with five stagehands, and we have extra people that we pick up along the way.”

But sometimes the extra help proved to be no help at all. “There was one time in Leipzig when a bunch of kids who were supposed to help us unload saw that the truck was packed from top to bottom, front to back. They got on their bikes and they rode away, so it was just us,” Reynolds recalls, laughing. “Touring’s hard but it’s been great. It’s always an adventure.”

Reynolds has plans for his retirement. “Once I leave here it will be a shock, but I’m sure I’ll adjust. I have a beautiful grandson whom I want to spend more time with. I’ll probably play more golf, although some people, like my wife, say I play too much now,” he says. “I’m hoping to come back here and work as an extra guy now and then. We’ll see how it all works out.”

Jack Zimmerman, who retired as customer relations manager of Lyric Opera of Chicago in 2014, is a Chicago-based writer and novelist.