Up until the outbreak of World War I, the roster of Chicago Symphony Orchestra musicians had primarily been European since its founding in 1891. The ensemble’s first two music directors—Theodore Thomas and Frederick Stock—were German immigrants, and their native language was spoken in leading rehearsals.

According to a report in the Chicago Tribune, tensions were high as the Orchestra performed works with strong nationalistic themes at a Ravinia Park matinee on August 14, 1914. Russian musicians taunted a Frenchman after Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture; Belgian principal clarinet Joseph Schreurs, “gritted his teeth as the musicians next swept through Die Wacht am Rhein,” a German patriotic anthem; and “several Germans snapped the strings on their violins while playing La Marseillaise . . . Quarrels arose [and] internal strife, fanned by patriotic fervor, threatened to disrupt the organization.” The article is here.

At the annual meeting of the Orchestral Association in December 1917, board president Clyde M. Carr addressed rumors regarding Orchestra members’ patriotism, reporting, “out of approximately one hundred members, there are only two who have not taken out their final papers,” completing their American citizenship. “There is no orchestra in America more unimpeachable in its Americanism.”

On April 6, 1918, Orchestra musicians drafted a resolution affirming their loyalty to the U. S. Charles Hamill, first vice president of the board, read the resolutions to the audience at that evening’s concert, declaring the Orchestra faithful to America “from the conductor to the kettle drum.”

While at Ravinia Park on August 6, 1918, seven members of the Orchestra were served notices to report to assistant district attorney Francis Borelli the following day, to answer charges that they had expressed pro-German sentiments. Accusations had been submitted against orchestra manager and trumpet Albert Ulrich; principal timpani Joseph Zettelmann, who had expressed contempt for The Star-Spangled Banner; trumpet William Hebs, who refused to stand during the anthem; and bass trombone Richard Kuss, who reportedly said he would kill any son of his who learned English. The article is here.

An August 16, 1918, letter to the Chicago Tribune editor expressed subscribers’ “faith in the loyalty of the majority of the members of the Orchestra.” The article is here.

Following the investigation, on October 10, 1918—the day before the first concert of the Orchestra’s twenty-eighth season—the Chicago Federation of Musicians announced that oboe Otto Hesselbach, bassoon William Krieglstein, bass trombone Richard Kuss, and principal cello Bruno Steindel were expelled from the union. All four had been tried on the same charge: “acting in a manner derogatory to the interests of the local and its members through unpatriotic actions and utterances.” The article is here.

In February 1919, the Chicago Federation of Musicians recommended conditional reinstatement of Hesselbach, Krieglstein, and Kuss, but not Steindel. Hesselbach and Krieglstein complied; Kuss did not. The article is here.

Otto Hesselbach (1862–?) was hired by Theodore Thomas in 1893 as oboe and principal english horn, and he also was occasionally listed as a member of the viola section. He was reinstated to the Orchestra in 1919 and served until 1928.

After emigrating from Austria in 1907, William Krieglstein (1884–1952) moved to Chicago and joined the Orchestra in 1912 as bassoon and principal contrabassoon, and beginning in 1915, he also was rostered as a bass. After his reengagement in 1919, Krieglstein was a member until 1929.

Richard Kuss (1883–1957) came to the U.S. from Germany in 1907 and served as bass trombone from 1912 until 1918. He was reinstated to the union in 1919 and remained in the city, primarily working for the Chicago Opera, but was not reengaged by the Orchestra.

Former principal cello of the Berlin Philharmonic, Bruno Steindel (1866–1949) had played under Brahms, Dvořák, Grieg, Richard Strauss, and Tchaikovsky when he was chosen by Theodore Thomas as the Chicago Orchestra’s founding principal cello in 1891. Following the investigation, he tendered his resignation on October 1, 1918. Steindel continued to perform in Chicago, as principal cello of the Chicago Civic Opera and giving concerts for the benefit of German war orphans, despite protests by American Legion posts. The article is here.

Steindel’s wife Mathilde, a pianist who frequently performed with the Steindel Trio (along with CSO violin Fritz Itte), had become depressed over the countless accusations her husband had received in the press. On the evening of March 5, 1921, she committed suicide by drowning herself in Lake Michigan. The next morning at the foot of Farwell Avenue, the police found her automobile, its lights “still ablaze. Her expensive fur coat, which she had cast off before jumping into the lake, lay on the pier.” The article is here.

____________________________________________________

A Time for Reflection—A Message of Peace—a companion exhibit curated by the Rosenthal Archives of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in collaboration with the Pritzker Military Museum & Library—will be on display in Symphony Center’s first-floor rotunda from October 2 through November 18, and the content also will be presented on CSO Sounds & Stories and the From the Archives blog.

This article also appears here. For event listings, please visit cso.org/armistice.

This exhibit is presented with the generous support of COL (IL) Jennifer N. Pritzker, IL ARNG (Retired), Founder and Chair, Pritzker Military Museum & Library, through the Pritzker Military Foundation.

Additional thanks to Shawn Sheehy and Jenna Harmon, along with the Arts Club of Chicago, Newberry Library, Poetry Foundation, and Ravinia Festival Association.

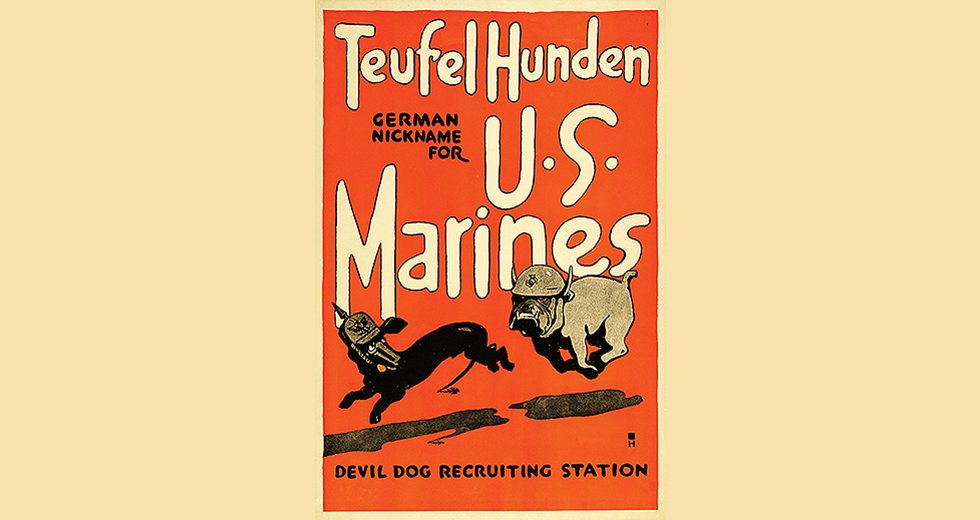

TOP: Teufel Hunden, Charles Buckles Falls. A “devil dog” bulldog wearing a U.S. Marine helmet chases a dachshund wearing a German helmet (U.S., 1917). | Image: Pritzker Military Museum & Library