Few figures stand taller in American musical history than Leonard Bernstein. The BBC Music Magazine cited him as the second-greatest conductor ever in a 2011 poll of 100 top maestros. His accomplishments on the podium alone would have guaranteed him lasting fame. But Bernstein was also a landmark composer of both Broadway and classical music, ranging from his merry 1956 operetta Candide to his massive Mass, a multifaceted theatrical work commissioned for the 1971 opening of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. If all that weren’t enough, he was a pioneering educator whose televised Young People’s Concerts in 1958-72 with the New York Philharmonic set the standard of how to introduce classical music to children in an intelligent yet compelling way.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Symphony Center Presents and Rush Hour Concerts are celebrating Bernstein’s still-vital legacy this fall with three complementary programs devoted to him and his music, ahead of his centennial in 2018. The lineup kicks off Oct. 23 with the CSO performing the composer’s score for “On the Waterfront” along with a screening of the Elia Kazan’s Academy Award-winning 1954 film. Then conductor Steven Sloane will lead the CSO on Oct. 24-25 in a Beyond the Score program titled “Bernstein in New York City.” It will combine a multimedia presentation on the multifaceted musician with an examination of Symphonic Dances, a 1961 suite drawn from the composer’s most famous work, West Side Story. The 1957 Broadway musical, a gritty, updated take on Romeo and Juliet, features lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, choreography by Jerome Robbins and a book by Arthur Laurents.

For its annual fall benefit, Rush Hour Concerts is presenting an evening of conversation and stories about the personal side of Bernstein, with performances of some of his lesser-known chamber music, show tunes and art songs on Nov. 10 at the Woman’s Athletic Club of Chicago, 626 N. Michigan. The evening’s headliner will be writer, broadcaster and concert narrator Jamie Bernstein, one of the celebrated musician’s three children. Also participating will be Rush Hour’s artistic leadership – violist Anthony Devroye, pianist Kuang-Hao Huang and CSO cellist Brant Taylor. (For tickets or other information, call [312] 640-7418 or visit rushhour.org.)

In advance of these concerts, Jamie Bernstein spoke to Sounds & Stories about her father, his love affair with New York City and his enduring influence:

New York City was Bernstein’s home for most of his adult life, correct?

That is right. His first big job in New York was as assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic, and before that, he was kind of scrabbling by. He had a little job at Harms-Witmark Music, where he did arrangements and transcriptions of material by [Aaron] Copland and even Coleman Hawkins, believe it or not. For the Coleman Hawkins transcriptions, he used the name Lenny Amber — a little known fact. Of course, being the assistant conductor is not a very illustrious gig, because conductors notoriously never get sick. So assistant conductors have to attend all the rehearsals and know everything that is going on and never get a chance to actually be on the podium. Except that on Nov. 14, 1943, the guest conductor, Bruno Walter, did get sick with the flu, and as we all know, Bernstein had to step in at the last minute. And the rest is history, as they say.

How would you describe his relationship with New York City?

I’m fond of saying that it was the only entity that could keep up with my dad. It was the perfect place for him to live. They were really made for each other, because my father never slept. He was a terrible insomniac. I’m joking about it, but it was actually a very debilitating condition. But the fact of the matter was that he had this engine, this motor that he couldn’t shut off. And so does New York City, so they were perfect for each other.

What were some of his favorite places there?

He was one of the early denizens of Carnegie Hall. He lived in one of the little studios that artists used to live in upstairs. Now all those spaces have been converted into [Carnegie Hall’s] education department, so it’s completely different up there. But that’s where he used to live, so he lived in that neighborhood and was a frequent visitor to the Russian Tea Room, which back then was where all the artists hung out, all the musicians and everything.

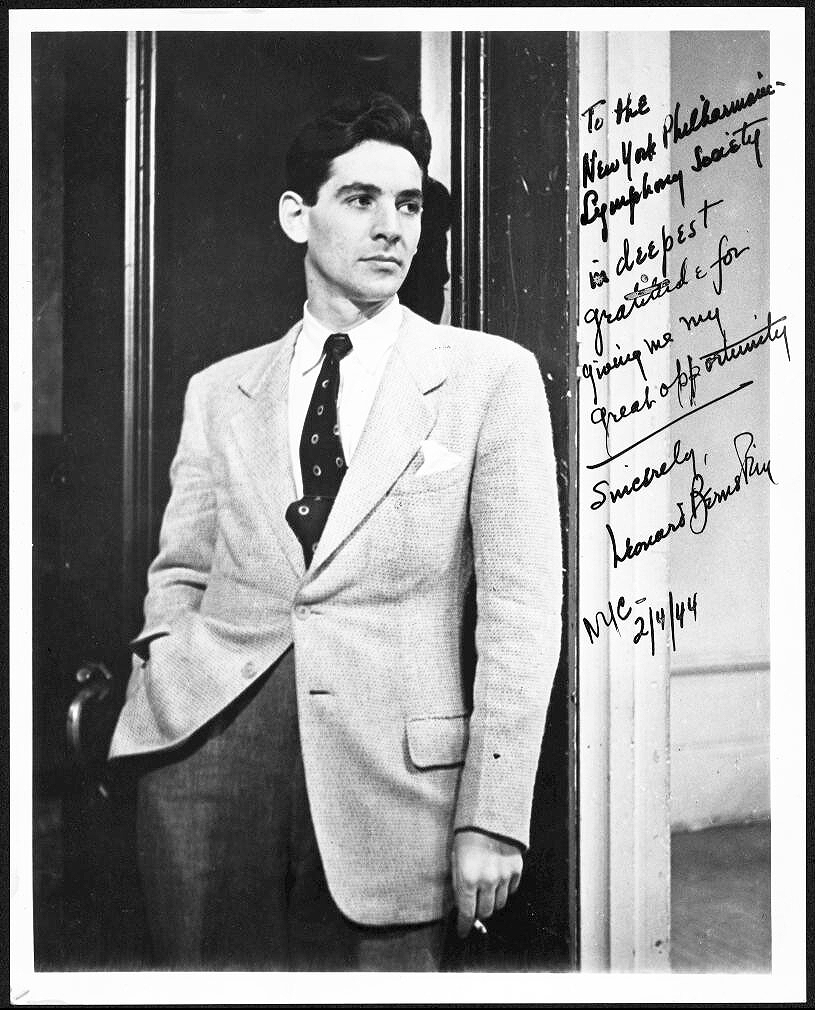

A few months after his NY Phil debut, Leonard Bernstein sends his regards for his big break. | Photo: Library of Congress

In fact, a story goes that one day there was a knock on the door of his studio in Carnegie Hall. It was this young ballet dancer by the name of Jerome Robbins, who had heard that Bernstein was a composer and might be interested in writing the music for this idea he had for a ballet about three sailors on shore leave in New York City. And my dad said, “That sounds interesting. Let’s go down to the Russian Tea Room and grab a bite and we’ll talk about it.” So Robbins was telling him his idea about the three sailors and how he wanted something jazzy and contemporary and that really gave the feel of how people moved in those days. My dad said, “Oh, that’s funny, because just this morning, this tune came into my head, and it goes like this. Give me your napkin.” And so he scrawled on the napkin [Jamie then sings a bar or two from the opening theme of Fancy Free], which is how [the 1944 ballet] Fancy Free begins, and Jerry reportedly said, “That’s it. That’s just what I had in mind.”

So the Russian Room was one of the haunts, and so was Nedick’s, which was like this coffee shop that I think in those days was just across from Carnegie Hall. It’s no longer there. We lived in the Osborne, which is just catty-corner from Carnegie Hall. That’s where we lived until I was about 9 years old. There was a Nedick’s there when I was a kid, and it had a little toy train that went around in a circle above the counter. So I was completely enchanted with the train, and I would wait for it to come back around.

How did New York City influence Bernstein’s music?

Well, look at how many pieces he wrote that were situated in or had to do with New York City. Three of his musicals, On the Town, Wonderful Town and West Side Story are all set in New York City. “On the Waterfront,” his one and only film score, is also supposedly taking place in New York City, even though it was filmed across the Hudson [River] in [New] Jersey. But it’s supposed to be in New York, so there’s that, too.

Is it safe to say that West Side Story is his most famous New York-related piece?

I would say that West Side Story is his most famous piece, period, quite apart from the New York City connection.

Were you alive when your father was writing West Side Story?

Yeah, I was awfully young. I was really just a toddler. So I don’t remember anything much, except that I do have vague memories over the course of my early years of my father in his studio in our apartment at the Osborne with Steve [Sondheim] and Jerry [Robbins] and Arthur [Laurents] in a cloud of cigarette smoke. That’s all I remember.

Do you have any memories of that piece or of your father and his relationship with that music since that time?

Leonard Bernstein gathers his family, including wife Felicia and children Jamie (center) and Alexander, around the piano for holiday music-making in 1955. | Photo: Library of Congress

It came into our lives so young that sometimes my brother and sister and I say that West Side Story is like our fourth sibling, because it was just always there and we grew up with it. But I didn’t really focus on West Side Story and really absorb it entirely until I was older. I was so young when it came out that my parents didn’t even take me see it on Broadway, because I was too young, and it was too intense with the knife fights, the gunshot and everything. That was really not cool for a 5-year-old. But I did have the recording on my little record player in my bedroom growing up. So I knew the music by heart, but it wasn’t until the film came out five years later that I really glommed onto it. My dad was ambivalent about the film. He did not love it. He was too busy to be hands-on about how the music was presented in the film. There were some arrangements that were done specifically for the film by Johnny Green, and my father gave permission for that to happen, but he wasn’t too thrilled with the results. But he kept it to himself. Since he couldn’t really take the time to be on top of it, he felt he didn’t have any right to complain.

Why does that music remains so captivating? It seems as fresh and contemporary today as when it was written.

I know. It is amazing. All I can say is, it’s kind of a mystery. Why are some pieces indelible and others aren’t? There’s an element of magic to it that we cannot account for. Why are some people geniuses and others aren’t? I don’t know. But when it comes to West Side Story, it was just such an amazing alignment of the planets that these four unbelievably talented artists all came together at the same time to put this show together, and that every aspect of the show was at its optimum — not just the score but the book and the choreography and the direction and the lyrics and everything. It just all came together. As for the score, I mean I don’t know. The essential idea that my father had was to tell the story through the music by having be-bop jazz represent the Jets and all this Latin-Caribbean music represent the Sharks. It was such a natural fit, and it so perfectly illustrated the contrasting energy of the two gangs, and all the love music is so gorgeous. All the elements came together in this magical way.

What would Bernstein think of today’s New York City?

I think there are a lot of things he’d love about New York. The energy remains the same. Central Park is still gorgeous, and everything is a lot cleaner than it used to be back in the ’70s and ’80s. I think he’d appreciate that. And I think he’d be so thrilled about what happened with the Supreme Court this summer with gay marriage being legal and how that has just liberated New York and all the other cities into this very happy place for a lot of people who weren’t happy in the past. I think he would be just amazed and overjoyed by that aspect of things.

With the approach of the 100th anniversary of Bernstein’s birth, his influence seems as strong as it has ever been.

I agree. I think it just keeps getting stronger. The further away we pull from the 20th century, the more influential and powerful my father’s legacy seems to get. It was just luck of the draw, but the years that he was composing were also the years when there this kind of straitjacket about the kind of music that you had to write if you were to be taken seriously as a so-called serious composer. Everybody had to write 12-tone music. As the conductor of the New York Philharmonic, he went out his way to advocate for contemporary music and present a lot of new works, and they were pretty much all 12-tone music. It was this weird corner that serious music had painted itself into by the mid-20th century, and my father as a composer was not interested in writing 12-tone music exclusively. He knew how to do it, and it was one of the many colors on his compositional palette, but he didn’t feel compelled to write that way the whole time. As a result, he was not taken seriously as a composer by the pundits in academic musical circles, because he kept defaulting to writing a tune.

But the further away we get from that part of the 20th century, the better my father’s music sounds. He was the one who stuck to his guns and wrote the music that he felt he wanted to write emotionally, and his music has so much emotional power in it. And so, it just sounds better and better to our ears with the passage of time.

Kyle MacMillan, former classical music critic of the Denver Post, is a Chicago-based arts writer.